Quick Post: Whither Central Bank Independence?

The Revenge of the Monkey's Paw

During my PhD, a recurrent complaint I had when studying Macroeconomics was that it really should be called Rich World Macro. Independent central banks, solidly anchored inflation expectations, and the steady rule of law are institutions particular to a small club of advanced economies. A more realistic and globally representative macroeconomics would engage with the institutional messiness of developing contexts—most of all, the political-economic pressures that most central banks face.

Somewhere, as I griped, a monkey’s paw curled.

As we react to Monday night’s news, I thought a quick post on what we know about central banks in developing countries would be a useful intervention.

The March of Independent Central Banking

Davide Romelli at Trinity College Dublin has made a career out of measuring central bank independence around the world. His global dataset on de jure Central Bank Independence will, I’m sure, soon be much-downloaded.

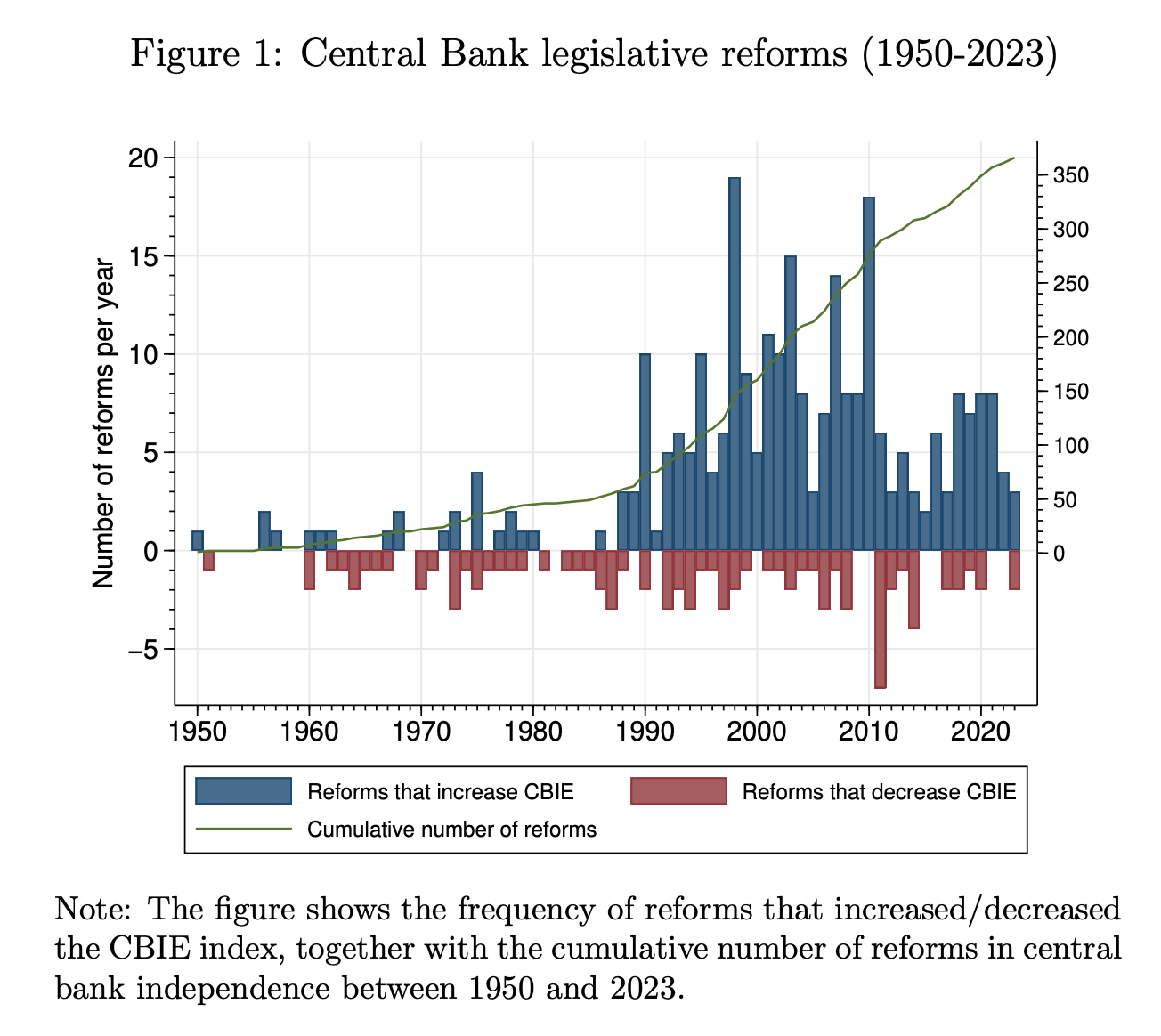

Romelli (2024) documents that, since the 1990s, the world has seen a general trend towards central bank legal independence:

The peak of these reforms was in 1998, when the European Central Bank took over monetary policy in the Euro Area. But this reform process was not restricted to poor countries. In the age of the Washington Consensus, developing countries also increasingly adopted reforms towards central bank independence, captured here by Romelli’s Central Bank Independence index:

Surely no small part of central bank reform has been, to use Lant Pritchett’s phrase, isomorphic mimicry—the de jure replication of the form of rich-world institutions, if not quite their function. With the United States trending in the opposite direction, I’m doubtful that this wave of reform will be fully reversed, but it seems like a fair bet that would-be autocrats around the world will look at Trump’s growing influence over the Fed and start getting ideas.

You Don't Know What You've Got Till It's Gone

But, beyond mimicry, another reason central bank independence has become so widespread is that it actually seems to, well, work.

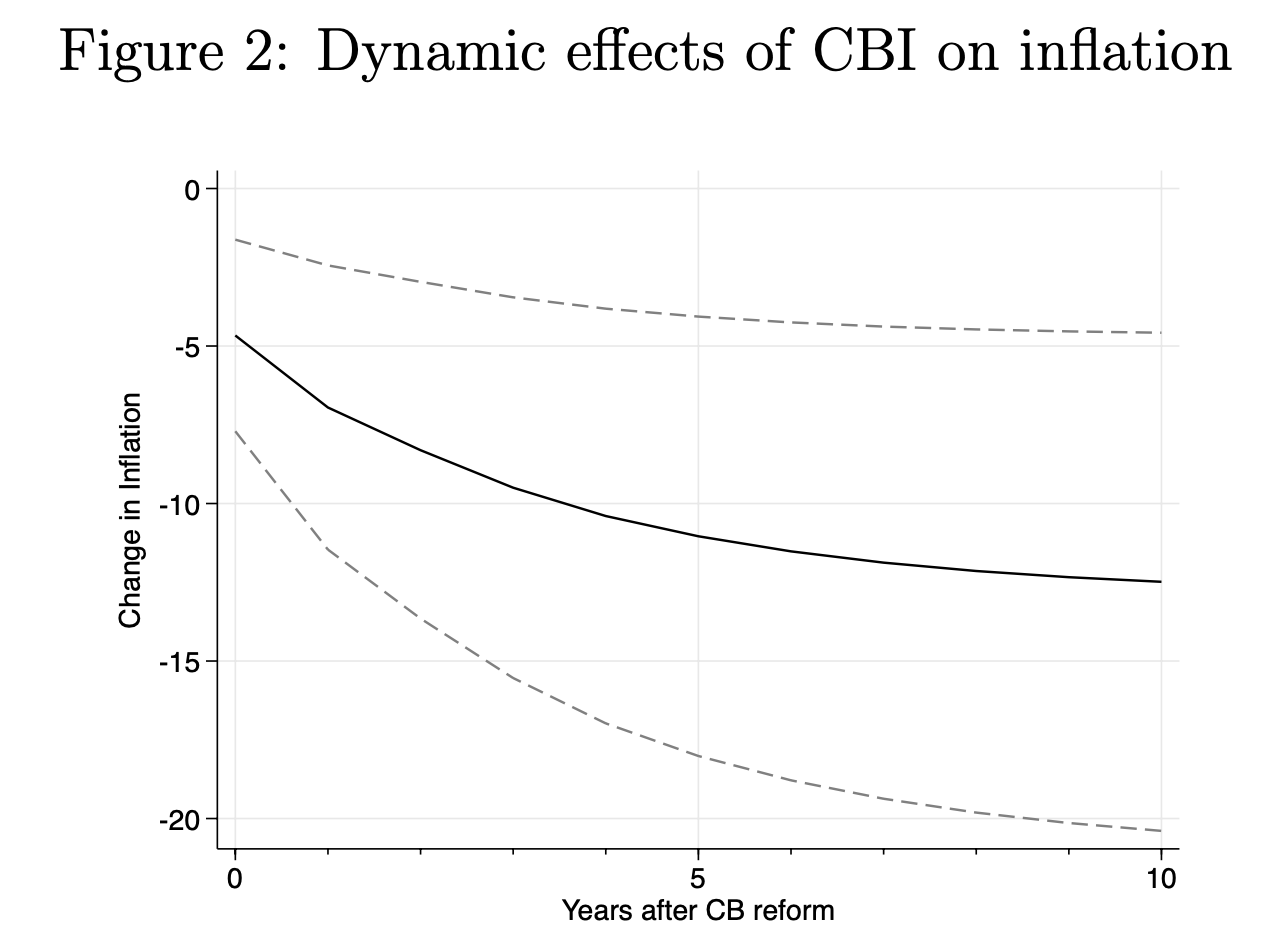

Athanasopoulos, Masciandaro, and Romelli have a well-timed April 2025 working paper showing that central bank independence has a long-run negative effect on inflation, averaging more than 10 percentage points over 10 years:

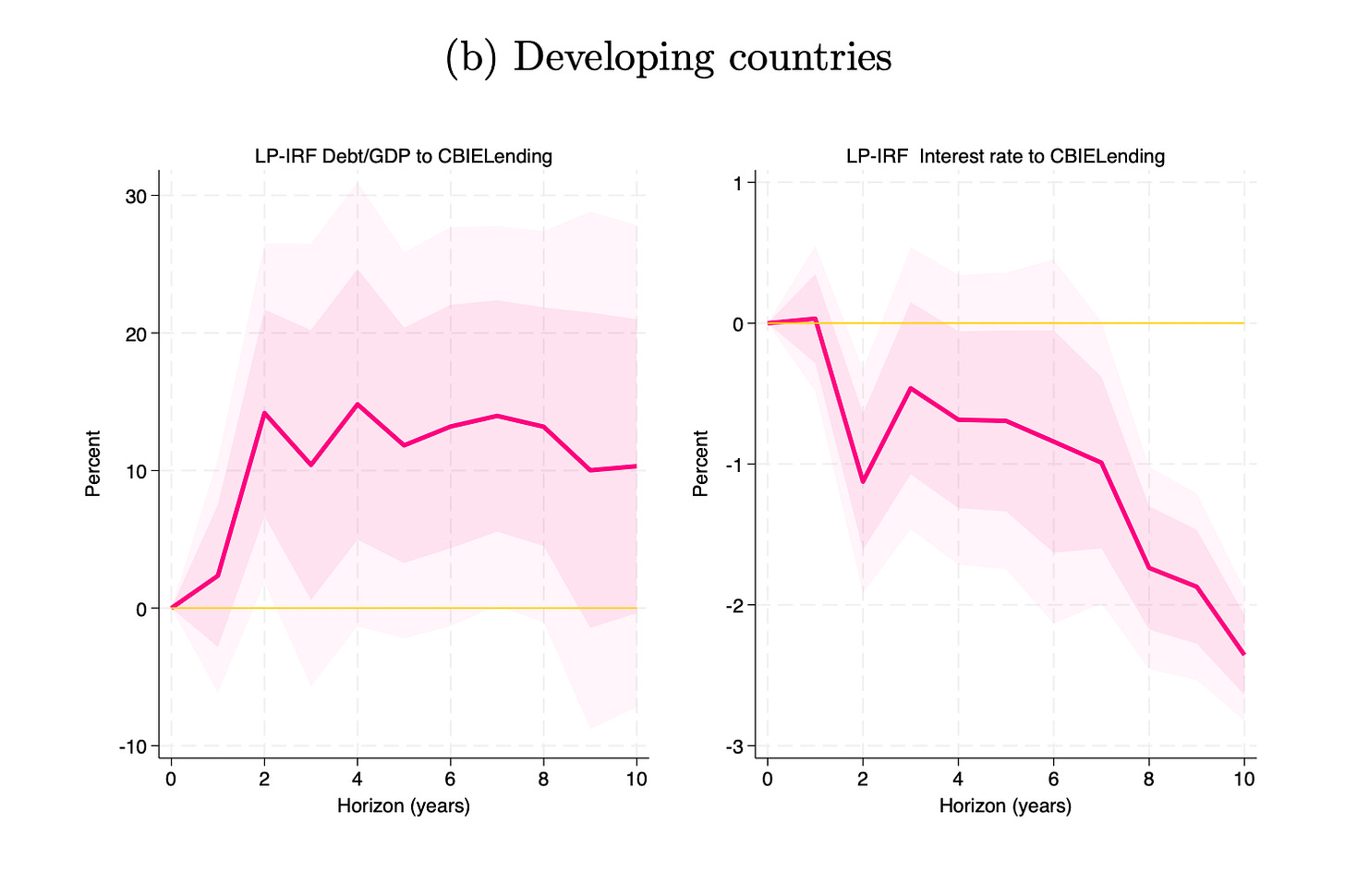

Similarly, Athanasopoulos, Fraccaroli, Kern, and Romelli have a working paper showing that higher restrictions on a central bank’s ability to lend to the government (i.e., greater independence) means higher debt-to-GDP and lower interest rates in developing countries:

The authors' intuition is that central bank independence appears to help poorer countries sustain higher debt loads without increased borrowing costs—which would make sense if one’s constrained oneself against the temptation just using the central bank to finance the debt.

The results of these working papers are far from final, so they’re worth taking with a grain of salt. (Arguing for a true, exogenous “natural experiment” in a time series macro setting is always a tricky business.) My gut sense is that an effect size of 10 percentage points of inflation seems quite high.

It’s also important to note that, up to this point, we’ve considered only de jure reforms. Romelli’s Central Bank Independence Index measures legal characteristics like who gets to appoint the central bank board, the level of required disclosure, etc. These do not capture all the other kinds of malfeasance and informal shoulder-leaning that can transpire outside the letter of the law.

A good example of that, in a working paper that will surely be getting a lot of press, is Drechsel (2024). Using a remarkable dataset compiled from presidential diaries, Drechsel analyzes the effect of political pressure on Fed behavior—in particular, Nixon’s 1971 pressuring of Fed Chair Arthur Burns to ease policy to aid his 1972 reelection. According to Drechsel’s data, Nixon met Burns 34 times(!) in the latter half of 1971. (By comparison, Bill Clinton met with Fed officials a total of 6 times during his presidency.)

Burns appears to have complied—in the Romer and Romer (2004) dataset of monetary policy shocks, the Fed Funds Rate was hit by a negative 150 basis point shock. In a straightforward event study, Drechsel finds a significant ~2 percentage point increase in the price level several years after the shock:

Embedding this event study into a model estimated on the broader sample of Fed-Presidential interactions, Drechsel finds that “exerting political pressure 50% as much as Nixon did, over a period of six months, permanently increases the U.S. price level by more than 8% after several years”.

These graphs remind us that the effects of interfering with central banks, like all monetary policy, can appear with long and variable lags. But if the empirics of central bank independence are to be believed, expect higher inflation and higher borrowing costs on the horizon.

Silver Linings?

That’s all rather gloomy. Do I have a silver lining to offer?

In his survey of central banking reforms, Romelli (2022) offers one. Central bank reforms, he argues, are an endogenous development after periods of high inflation—an institutional solution to a perennial economic problem.

If we go further down the road of lessened Fed independence, the good news is that, if developing countries are any guide, that these institutions can re-emerge. The bad news is that it may take long bouts of economic pain to remind ourselves why we had them in the first place.

The fact that central bank independence allows governments to borrow more at lower borrowing costs is not remotely surprising. This is literally why England was able to win so many wars.

Also if central bank independence isn't possible in the 21st century we should simply go back to free banking which is a much more moderate risk strategy as opposed to the inherently high risk strategy of central banking.