The S-Word

Review: Sheri Berman's The Primacy of Politics: Social Democracy and the Making of Europe's Twentieth Century

The Primacy of Politics: Social Democracy and the Making of Europe's Twentieth Century, by Sheri Berman. 2006.

When the Revolution comes, I know I’ll be first against the wall as a capitalist roader—or if my executioners are being pedantic, a Bernsteinian Social Democratic Revisionist. As a former Fed employee and Goldman Sachs intern, I've long since booked my spot at the front of the line. So I hope I'm not revealing anything new when I say that I enjoyed Sheri Berman's The Primacy of Politics, which argues forcefully that social democracy was largely responsible for the flourishing of postwar Europe.

Social democracy is the awkward middle child of ideologies. It's what most well-meaning urban twenty-somethings probably believe in, but it lacks the kind of hefty ideological book that supports more extreme views, like Marxism or Libertarianism. (Karl Polanyi's The Great Transformation probably comes the closest.) Naturally, young social democratic nerds are at a disadvantage in high school intellectual combat, when the Libertarian nerds pummel them with their dogeared copies of Atlas Shrugged, take their lunch money, and then solemnly trace the sign of the dollar in the sky.

But what social democrats have instead of theoretical consistency is a real track record at delivering equitable, generally happy societies. The Primacy of Politics follows the intellectual and political history of the social democrats and their forebears, to show how these places were made. Rather than recount the full historical play-by-play, I’ll summarize three of her big themes.

Ideology Matters

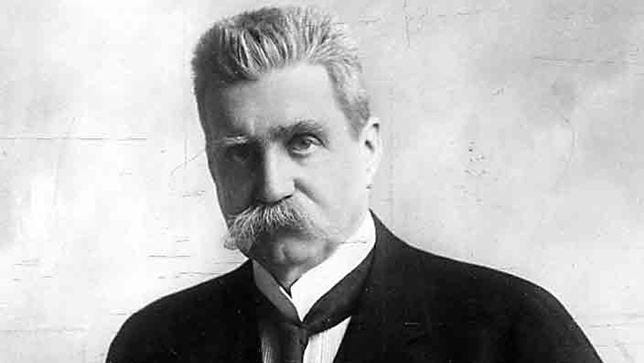

The first is that ideology matters, and a foolish attachment to theory over reality can wreak serious political damage. Orthodox Marxism is historically determinist, believing that the actions of individuals and political parties are ultimately irrelevant for change—the impersonal forces of economic development will necessarily bring about socialism. When the revisionists led by Eduard Bernstein split from mainline Marxism at the turn of the 20th century, they argued that the facts behind this theory had changed: capitalism was far from its death throes, and there would be no inevitable tide to carry Europe to socialism. Instead, socialists would have to achieve it themselves through reform and political action.

Though influential, these views were pilloried by the socialist establishment of the time, many of whom still held on to the magic of historical determinism. So when the turmoil of the First World War swept socialist parties to their first electoral victories, actual power came as a surprise. Lacking a specific program of change, they fumbled on passing major reforms. In France, the socialists refused to participate in government, producing a succession of unstable cabinets that satisfied no one. In Italy, unwilling to “make” its own revolution, the socialists even refused to lead a nascent worker’s council movement. In Germany, perhaps the worst example, the Social Democratic Party (SPD) nixed the 1931 WTB Plan, a deficit-financed work creation program, on the grounds that such an “offensive economic policy” was “un-Marxist” and contrary to the historically determinist “logic of capitalism”. Only after the disasters of fascism and another world war did the SPD shed its commitment to orthodox Marxism—in 1959.

Fascism and Socialism

How did these disasters come about? Berman’s second big theme is how the Right can undercut the Left’s appeal by stealing its economic ideas. The book’s best chapters trace the common intellectual roots of fascism, national socialism, and socialism. Inspired by the swelling nationalism around World War I, thinkers like Hendrik de Man and Benito Mussolini took socialist ideas but replaced notions of class struggle with those of national and, later, race-based identity. Gradually more and more of the bits about actually helping the poor were shed, but a core of “working for the common good” always remained—and proved to be political dynamite.

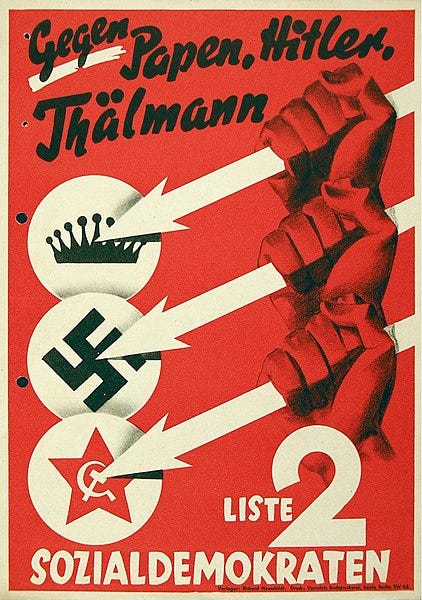

When the Depression hit, the Nazis pursued vast public works programs to fight mass unemployment. They even imported anticapitalist rhetoric to harness populist feeling without scaring off big capital: the Nazis distinguished between capital that was “rapacious”—financial, commercial, most of all Jewish—and “creative”—industrial, productive, Germanic. (Think also of today’s contrast between “globalists” and “job creators”.) Antisemitic rhetoric like this helped justify the theft and violence that underwrote generous public spending, which was immensely popular with the public. Compare this with the anemic response of the German SPD, who reluctantly supported painful austerity in the name of saving the ailing republic. In the mind of the “average” German, who was working for them?

The Primacy of Politics

Which leads to Berman’ third and final theme, the titular primacy of politics. I’ve already discussed one aspect—trying to actually effect change through democratic politics, rather than sitting around waiting for spontaneous revolution like the return of Lord Xenu. But if you disavow revolutionary violence, how can you bring about change?

A core tenet of Marxism is class struggle—labor against capital. But by the 1920s, it was clear that Marx’s prediction that most of the population would become proletarianized was not happening. This created an electoral conundrum for socialist parties, which were founded explicitly as worker’s parties. While the SPD consistently won pluralities in Weimar Germany, they refused to expand their appeals beyond their traditional base, and struggled to get more than a quarter of the vote. Potential middle-class and rural SPD voters were gobbled up by the Nazis, who in 1933 banned the SPD outright.

The successful counterfactual is Sweden. Under the leadership of Hjalmar Branting, the Swedish Social Democrats (SAP) took an early revisionist stance, emphasizing reform and political liberalization over Marxist determinism. Most importantly, they worked hard to grow their base beyond the industrial proletariat, bringing in small farmers and eventually even members of the middle class. The SAP increased state intervention in the economy and grew the welfare state by couching these moves in the language of Swedish solidarity—a “people’s home” where the state worked on the behalf of the “weak” and the “oppressed”.

Following the Swedish example, Berman’s overall conclusion is that that the better world that socialists dream of will have to be built reform by reform. She has two main recommendations. First, socialist governments should vigorously pursue policies that make people’s lives visibly better. Watered-down reforms—or worse, austerity—usually just leaves the Left holding the bag as second-rate members of the Establishment, exposing them to populist attacks from the Right. And second, more controversially, Berman argues that social democrats can perform an outflanking maneuver of their own—by responding to people’s genuine desires to belong to a specific community and couching their ideas in common national symbols and ideals, but leaving out the racism.

Socialism in America

Now, is any of this possible? Berman wrote this book in 2006—are we any closer to a communitarian social democracy in America?

The glib but honest answer is no. There is no broad-based political movement of working people to build a social democracy in the United States. This remains a deeply conservative country. In 2020, when Bernie Sanders led the Democratic primary for a brief few weeks—likely the farthest any self-proclaimed socialist has made it to the American Presidency—most of the core constituencies of the Democratic establishment rallied out of nowhere to clobber his campaign.

Now, was this because Sanders’s socialist policies were politically unpopular, or just because of the big red socialist label that came on the box? Surely at least partly the former. If I have a complaint about The Primacy of Politics, it’s that for a book with “politics” in the title, it rarely grapples seriously with the tradeoffs of winning elections. For instance, in Berman’s account, victory for social democrats was the natural product of (1) pursuing large-scale social reforms and (2) expanding cross-class appeal, without acknowledging how these objectives can sometimes cut against each other. When winning elections comes at the cost of cutting back some meaningful reforms, what is the correct balance to strike?

This question has no easy answers, not least in this country, where institutional bias and right-wing propaganda have stacked the deck against large-scale expansions of government. The 1990s neoliberal turn of Democrats and UK Labour, while electorally successful, went too far, blurring the distinction between Left and Right in the minds of voters. New cross-cutting cleavages (or rather, growing consciousness of old ones) like race, gender, and sexual identity also challenge Berman’s call for an expanded, cross-class movement united around a common identity.

But if there’s one clear lesson from this book, it’s that ideological consistency will be the easiest thing to lose. Decades after the Cold War, the S-word is just starting to lose some of its stigma among young people—but there remains a deep-seated antipathy that I think will be hard to break. Just as socialism lost its Marxist stripes to build the European welfare states, the only successful social democracy in America will likely be one that publicly disavows its intellectual roots: socialism in everything but name.

And that’s okay—it’ll be taking the lesson of this book, about the primacy of politics, to heart. In the end, only Bernsteinian Social Democratic Revisionist nerds like me will care.

As a Trotzkyst, I would point out two things. 1) I find that the likes of Lenin and Luxemburg tended to reduce issues of social transformation to the economy much less that Bernstein, who thought it possible to enact a transition to socialism through economic parliamentary reforms without a political (and violent) counterattack from the bourgeoisie. 2) I think that it's no coincidence that social democracies are (or were) an institutional reality in the Global North only.