Beyond GDP: One Table of Neoclassical Economics Solves the Europe vs. America Debate, For All Time, Forever and Ever, Amen

And some implications for development

There are lots of European students at UC Berkeley, and once we exhaust the usual stable of light conversation topics—the low quality of American bread—do we have to tip for takeout?—what is a Double Down, anyway?—as economists, we inevitably turn to macro comparisons.

On the one hand, America’s defects are now so glaringly obvious that they hardly bear repeating. We have a health care system that spends the most and achieves among the worst outcomes in the developed world. Inequality is high. Homelessness has been steadily increasing. Every four years, we flip a coin to find out if our government will be run by a lunatic.

On the other hand, as Matthew Yglesias points out, America is enormously wealthy—and the gap with Europe only seems to be growing. A Berkeley PhD stipend (an amount so low that it recently sparked the largest academic strike in US history) buys a decent living in many Latin American and European countries. And, of course, all the European grousing about overpriced baguettes would not be possible if said Europeans had not come to study at an American university.

As a Berkeley 20-something who likes public transit and François Truffaut, my sympathies are probably no mystery. But is there a way to think more systematically about these kinds of comparisons?

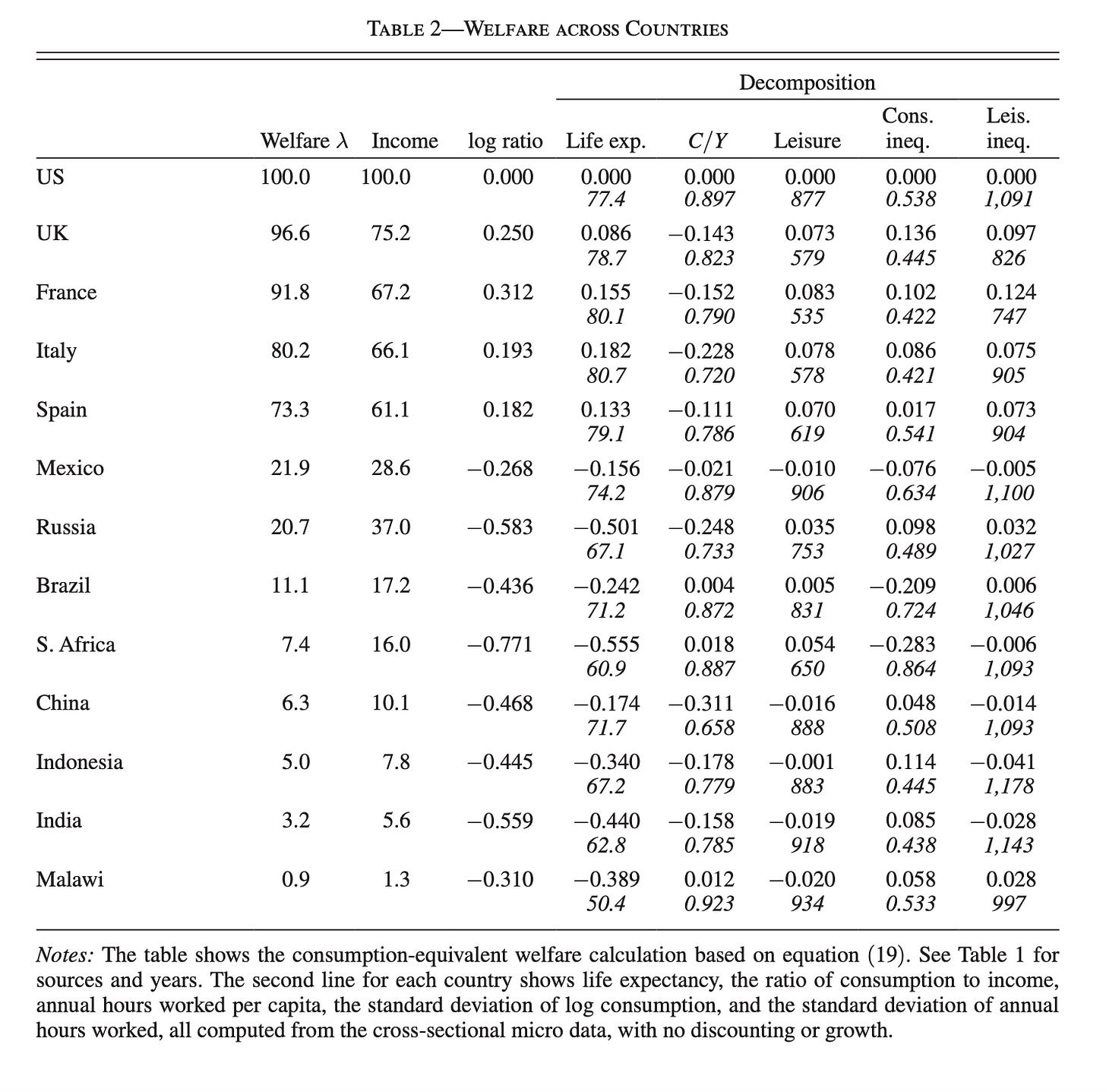

Almost every day, I find myself thinking of this table from the 2016 paper “Beyond GDP?”, by Chad Jones and Peter Klenow, two Stanford professors:

Column 2 showcases the extraordinary wealth of the US. In the mid-2000s, average incomes in the UK were only 75% of US levels; average incomes in France were just 67%. These gaps have only widened over time, as America’s economy has grown while Europe’s has stagnated. But most of the counterpoints to Yglesias’s argument are also in the table—Americans live shorter lives, experience higher inequality, and work more than their peers in other rich countries.

Jones and Klenow channel these disparate facts about incomes, inequality, and health through a neoclassical economic model, letting us make systematic welfare comparisons across countries—to go beyond GDP. And the results, especially if you’re of a neoclassical persuasion, are surprising.

Let me walk you through it.

Some not-so-unpleasant arithmetic

Jones and Klenow build their paper around a thought experiment: if you were one of the luminous unborn spirit critters from Pixar’s Soul, unsure of where in society you would fall, in which country would you choose to be born?

It’s an old thought experiment, dating back at least to John Rawls and his famous veil of ignorance. But, being economists, Jones and Klenow express this problem mathematically, with this utility function:

In plain English, this equation says that each year, your utility u will be higher the more you consume (C) and the more leisure time (l) you have—provided that you are not dead (probability S). Note that consumption, not income or GDP, goes into the function—what you consume, not what you earn, is what matters. Take those yearly utilities, sum them over the 100-odd years of your life, and that’s your lifetime “welfare”. From behind the veil of ignorance, all of us can expect to be an average person—and time and chance happeneth to us all—so to denote that these are all random variables, an expectations operator E goes on the outside.1

We need one last bit of algebra to compare “welfare” across countries. Simply comparing Us is largely meaningless—we know that people prefer higher values of U, but it’s hard to say what one unit of “utils” really means.

To put things into a common, interpretable scale, Jones and Klenow pose another thought experiment: as a unborn soul placed in the US, the highest-welfare country, how much consumption would we have to take away from you for you to be willing to switch places, and be born somewhere else?

We can this express with the same equation, except we multiply consumption C in the utility function by a factor λ, which is how much income you’d get to keep in this thought experiment.

λ, which the authors call consumption-equivalent welfare, collapses all the different factors we’ve been discussing—life expectancy, consumption, income—and combines them with the machinery of the neoclassical model into a single number, which we can use to make cross-country comparisons. Now we can finally unpack the table.

The Lambda Factor

Hopefully, the Jones and Klenow table is starting to make more sense. In the right set of columns we have the key model inputs: life expectancy, consumption as a share of income (C/Y), and leisure time (reported inversely, as hours worked). We also have inequality in consumption and leisure, which don’t enter the utility function directly, but do end up mattering when we take the expectation (loosely, if where you’re born in the distribution is a matter of chance, greater inequality lowers expected welfare).

The top line in each row shows how much each variable contributes to welfare differences; the bottom line shows the raw data. For example, the UK has higher life expectancy than the US (78.7 years versus 77.4), and significantly more leisure (579 hours worked versus 877). Nobody works less than the French, who work a blissful 535 hours a year per capita.

Column 1 is the punchline. We plug all these components into our utility equations, and figure out the percentage of consumption 1 - λ we’d have to take away from you for you to be willing to be born elsewhere. Consumption-equivalent welfare in the United States, as the highest-welfare country in the sample, is automatically set to 100, and every country is listed relative to that. So consumption-equivalent welfare in the UK is 96.6% the US level; in France, 91.8%; in Italy, 80.2%. In other words, I would have to take away 3.4% of the average American’s lifetime consumption (100% - 96.6% = 3.4%) for them to be willing to be born in the UK, and 8.2% to be born in France.

That’s not much of a difference at all.

It’s even more striking when you remember that Column 2 says that incomes in the UK are only 75.2% of the US level; in France, only 67.2%. The welfare differences between the US and its peers in our neoclassical model are much smaller than the income differences. The French earn almost a third less in income than the Americans, but their consumption-equivalent welfare is only 8% less. Italy and Spain see a similar boost in welfare relative to their income levels, though the size of that boost is smaller than France’s.

What’s going on? Europe’s better social outcomes are pulling welfare upwards. Americans make more money and consume more, but they have less leisure time and live shorter lives. All the money in the world means very little if one is not around to enjoy it. Moreover, Americans experience greater inequality in the amount of consumption and leisure time: all else equal, souls choosing their birthplace from behind the Rawlsian veil of ignorance would prefer a place with lower levels of inequality, to avoid the downside risk of being born at the bottom of the distribution.2 For the European countries, higher life expectancy and lower inequality are the main drivers of the gap between incomes and welfare (a divergence summarized by the log-ratio, in column 3).

I like this paper so much because it takes the neoclassical model on its own terms, and asks the question: if we truly believe the model, what kind of society should we value? The utility functions above are workhorse, standard, neoclassical—there are no behavioral quirks (like, say, altruism), no deviations from strict economic rationality.

But even within the strict framework of standard neoclassical theory, better social outcomes can erode large income differences. Now imagine what happens when we start to take off those theoretical blinders. The Jones and Klenow calculations rest on specific assumptions about utility: if you chose a function that placed a greater weight on leisure, or one where the benefits of more consumption diminished faster, or one that placed greater value on, you know, being alive, then the gap between Europe and the US would shrink even further—and perhaps even flip. This is to say nothing about people’s preferences for equality, beyond a personal concern about where you might be born into the income distribution. All the prosperity in the world feels rather hollow when one sees people without homes, pushing shopping carts past gleaming corporate HQs.

Jones and Klenow came out in 2016, based on statistics from the mid-2000s. Since then, the US’s income lead over Europe has widened, but inequality has also grown faster, and life expectancy has either stalled or gone backwards. It’s unclear how these factors net out, but my hunch is that the basic tenor of results will remain the same. If in a strictly neoclassical model, Europe and the US come out to a dead tie, imagine what would happen if our utility functions incorporated the freshness of the bread.

The Narcissism of Small Differences

You’ve probably noticed that I brushed rather carelessly past the bottom rows of Jones and Klenow’s table. Life in Spain, the poorest rich country in the sample, doesn’t seem that bad—it’s conceivable that someone would trade a quarter of their lifetime consumption to enjoy a pleasant life on a Mediterranean beach. In fact, many do.

But there’s a steep drop-off to the next country, Mexico, which only has 21.9% the consumption-equivalent welfare of the US. Russia is next, with incomes 37% of the US level but only 20.7% of the consumption-equivalent welfare. Most shocking of all, Malawi’s consumption-equivalent welfare is just 0.9% of the US level—in the thought experiment, I would have to take away 99.1% of an average American’s lifetime consumption for them to be willing to trade places with a Malawian.

Stare at this table for a while and little developmental vignettes start to emerge: China’s atrociously low consumption share (66%, the lowest in the sample); South Africa and Malawi’s tragically low life expectancy (just 50.4 years for Malawians), brought down by the HIV/AIDS epidemic; high consumption inequality in Brazil and South Africa, the only two countries more unequal than the US in the sample.

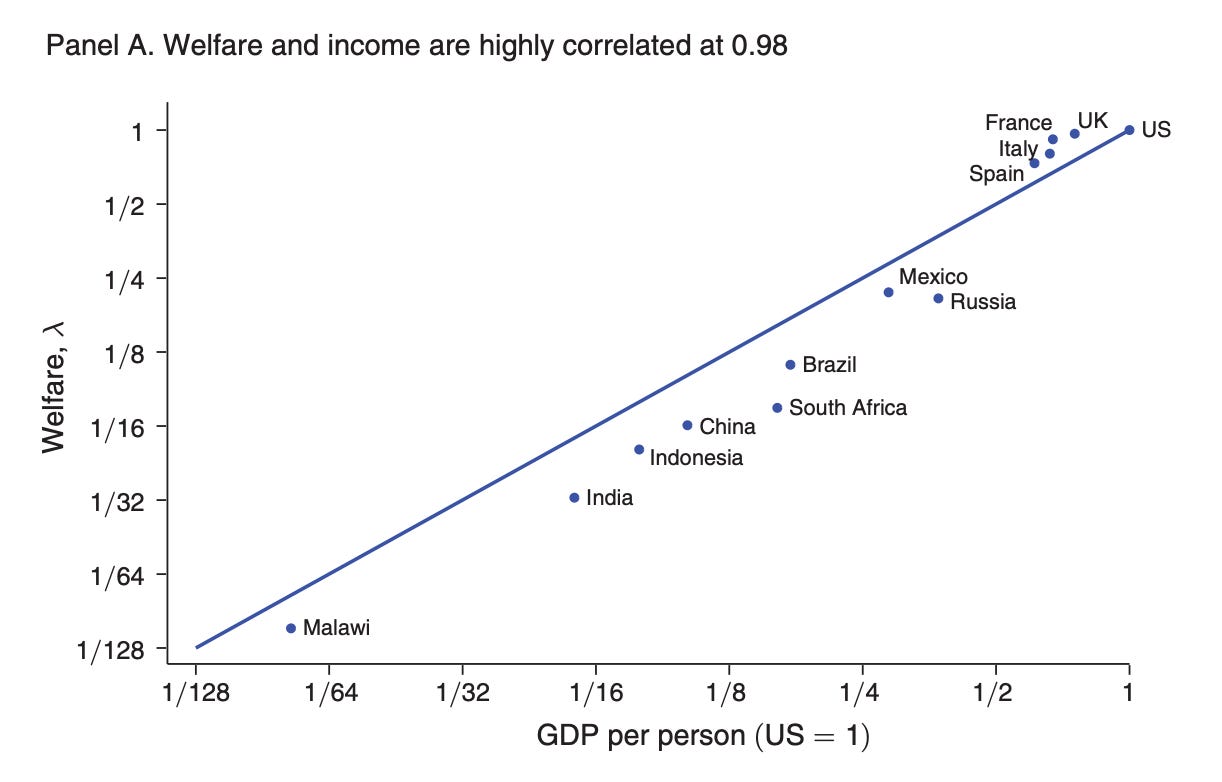

Confronted with these figures, the gaps between Western countries start to seem like the narcissism of small differences. The first-order concern remains that some countries remain incredibly poor—on average, incomes are still the main determinant of welfare across countries:

But a myopic focus on incomes would also miss some important details. In poor countries, unlike in rich ones, welfare relative to the US is lower than income relative to the US—social outcomes are so bad that they exacerbate the enormous economic gap. (In the graph above, all the poor countries fall below the line of best fit.) Malawians already barely earn more than 1% what Americans do; their consumption-equivalent welfare is less than 1% the US level. Riven by inequality and dragged down by poor life expectancy, South Africa’s consumption-equivalent welfare relative to the US is less than half its relative income; Brazil’s is around a third less. If what we care about is people’s welfare, not just the chasing of statistical glory, then there are large potential gains to be had by directly addressing these social needs.

Once you start thinking about growth…

One last note, for the macro-curious in the room.

Jones and Klenow didn’t invent the λ factor to get consumption-equivalent welfare—that trick was popularized by Nobel Laureate Robert Lucas in his 2003 American Economic Association Presidential address. In the second-most famous part of his speech (the first was his somewhat hasty proclamation that the “central problem of depression prevention has been solved”), Lucas calculated that, to eliminate all recessions in the United States, a representative agent should only be willing to give up λ - 1 = 0.0005, or 1/20th of one percent, of consumption. Compared to the problems of economic growth, Lucas famously concluded that the gains of better business cycle management were miniscule.

I don’t think that’s quite right. There are all sorts of things wrong with Lucas’s approach; recent work by Stéphane Dupraz, Emi Nakamura, and Jón Steinsson, with a more realistic model, lands on a figure that’s closer to 1.20% of consumption, an order of magnitude higher. My take is that strictly economic models like these still probably underestimate the overall effects of prolonged recessions. Depressions can lead to political upheavals with consequences far greater than a macro model can account for—for instance, the economic pain caused by fiscal austerity may have led to the rise of the Nazis.

But, if you’re willing to play a little loose with theory, you can think of Lucas and Dupraz et al.’s models as cousins of Jones and Klenow’s, and their welfare metrics as broadly comparable. Even if we imagined that the real “welfare cost to eliminate all recessions” was ten times Dupraz et al.’s estimate (and a hundred times greater than Lucas’s), the welfare cost of being born in a developing country like Brazil (88.9%) or South Africa (92.6%) is an order of magnitude higher than that. And, if you want to truly be utilitarian about it, this is before even taking into account how many more people live in the developing world. Think about an event like the rise of China, which (according to the official statistics) took 800 million people—more than the population of the US and the EU, combined—from an income level of around Malawi to that of Mexico.3

The scale is staggering.

Your takeaway shouldn’t be that ending recessions in the rich world is unimportant. It’s that, if we take the neoclassical model seriously, there are countries so poor that even rich world incomes in a deep recession would leave them many, many times better-off than they currently are. In Robert Lucas’s famous phrase, “once you start thinking about growth, it’s hard to think about anything else.”

The beta term, which I don’t cover here, is a discount factor, accounting for the fact that we prefer consumption today over consumption tomorrow.

Subject to assumptions about risk aversion, but that’s beyond the scope of this blog post. Also, Jones and Klenow explicitly use the welfare of the “average” person as their metric. One could just as easily focus on the welfare of the worst-off (as in Rawls’s original Difference Principle).

It’s worth noting that there is evidence that China’s social outcomes around 1980 were better than its income level would imply.

![Paris, Texas – [FILMGRAB] Paris, Texas – [FILMGRAB]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!7sVV!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fc380b66f-c854-451f-b49d-6b3354fd5b3a_1017x569.jpeg)

The Chinese families net worth is not several time that of US families. That's simply delusional

Very interesting paper. I'm interested in seeing how they get the utility of consumption or the disutility of working though. Some of it is going to be a consequence of the assumptions regarding the particular small u(), but not all of it