Review: How Africa Works

Joe Studwell Turns To Africa

How Africa Works: Success and Failure on the World’s Last Developmental Frontier, by Joe Studwell. Atlantic Monthly Press. 2026.

When Joe Studwell’s How Asia Works came out in 2013, it was a book deeply out of consensus. In an age of randomized control trials and micro-interventions, it resurrected macro policies—land redistribution, industrial policy—that had virtually disappeared from mainstream development economics. Moreover, it returned East Asia, the only developing region in the world to successfully make the postwar climb out of poverty, back to the center of debate.

Thirteen years on, Studwell probably deserves some kind of triumphal march. Industrial policy is back in a big way. Through How Asia Works’s influence on Noah Smith and a host of bloggers, a generation of young tech-adjacent males were primed to rant about semiconductor subsidies at parties.

I am no exception. Reading How Asia Works was a formative intellectual experience for me—a jolt out of the mathematical slumber of PhD coursework. I have a complex relationship with the text (more on this in a moment), but I still recommend it effusively to anyone who wants to learn about East Asia.

Now, thirteen years later, Joe Studwell is back. How Africa Works aims to do for Africa what he achieved for Asia—becoming the natural first stop for readers who want to learn about the economics of the continent.

A Dismal Inheritance

The first part of How Africa Works addresses the perennial question: why is Africa poor?

Historically, low population density, induced by pests like the tse-tse fly, discouraged the formation of large urban centers. The slave trade—first Arab, then Western—further depopulated the continent, breaking down social bonds. When Europeans arrived in force in the 19th century, they did colonialism on the cheap, with few policemen and even fewer schools. Unlike (say) the Japanese in Korea or Taiwan, the colonial state rarely penetrated much farther than the capital or key ports, leaving governance in the vast hinterland to invented or upjumped chiefs.

Decolonization left a dismal inheritance. In spite of superficial similarities in GDP with East or South Asia, Africa had far more problems on its plate. Levels of education were far too low to sustain an effective civil service, let alone communities of engineers or innovators. Incoherent states encased in inappropriate borders meant Africa’s founding fathers had to stitch nations together from unrelated ethnic groups.

Studwell’s diagnosis of Africa’s problems is steadfastly conventional, leaning heavily on the academic consensus established by Jeffrey Herbst, Robert Bates, Nicolas van de Walle, Leonard Wantchekon, among others. This is no dig; Studwell is an elegant synthesizer. I have some quibbles around the margins—the underrating of precolonial Africa reflects some lingering Western state-centric bias—but as a diagnosis for Africa’s poverty this is a far richer, textured, and more accurate account than the memelike “extractive institutions”.

Four Success Stories

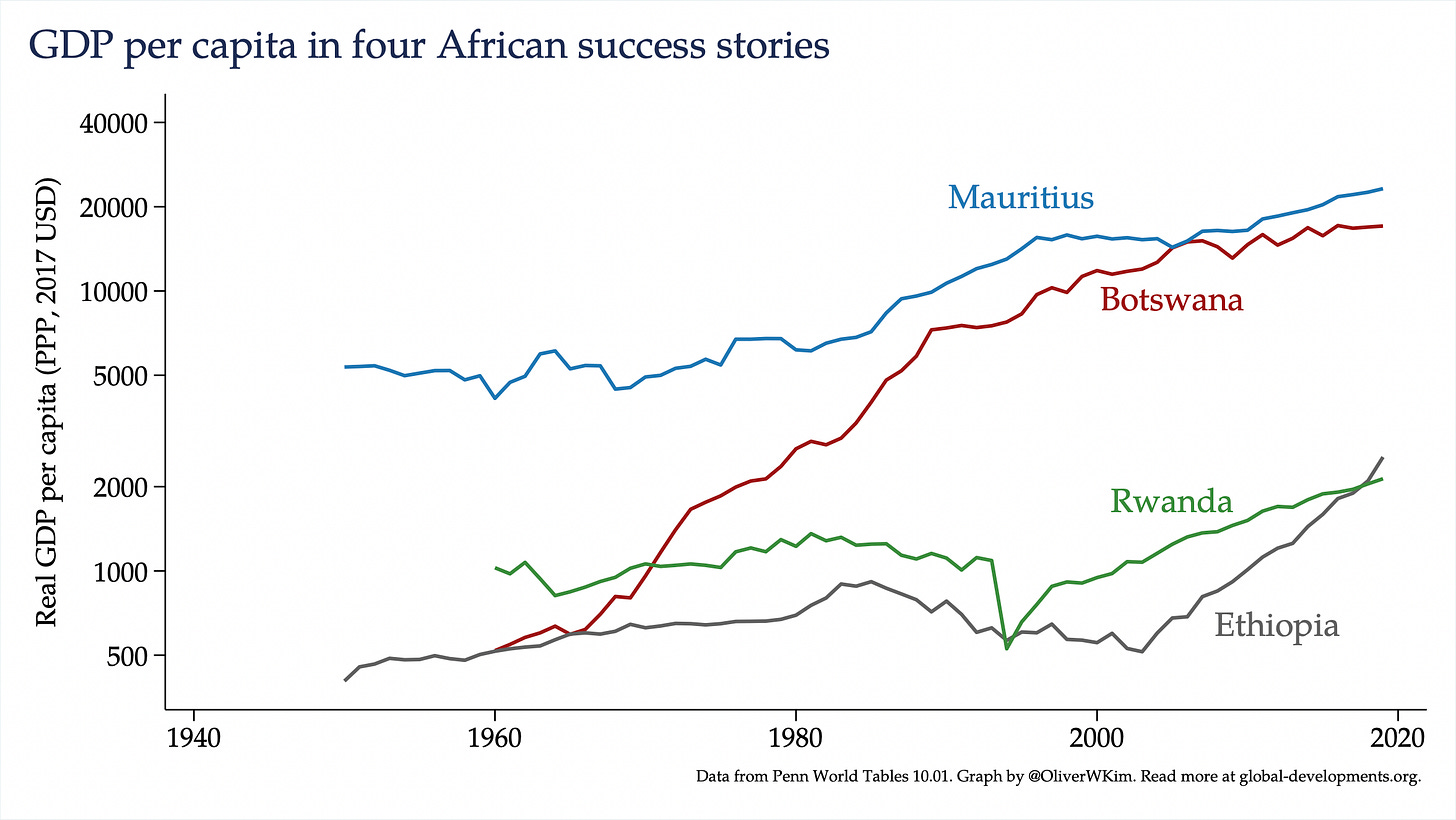

Having set the scene, Studwell turns to four successful case studies: Botswana, Mauritius, Ethiopia, and Rwanda. This itself is a refreshing approach to economic analysis of Africa, which so often wants to dwell on failure. Unlike Taiwan or South Korea, none of these countries is an unqualified developmental miracle, but their relative success provides clues to how an African economic transformation might take place.

Botswana

Botswana is Studwell’s poster child for a successful democratic developmental coalition. (For this reason, it featured heavily in Acemoglu and Robinson’s Why Nations Fail as an example of “inclusive institutions”.)

Under the sound leadership of Seretse Khama, local chiefs were carefully co-opted at independence and the Botswana Democratic Party built up into a genuine national force. Khama also created a capable civil service, initially staffed by remaining Europeans, but gradually Africanized with sterling Batswana talent. This meant that when diamonds were discovered just around independence, the windfall was carefully managed, avoiding the worst effects of Dutch Disease. These mining revenues helped raise Botswana to upper middle-income status, making it the fourth-richest country in continental Africa.

Botswana’s chief failing, in Studwell’s view, was adhering too much to responsible policy orthodoxy—i.e., not enough industrial policy. There was no vision for large-scale industrialization, no coherent plan to create large numbers of factory jobs. Moreover, the political dominance of large cattle owners (Botswana was a society of pastoralists rather than farmers) meant that redistribution was never in the cards. The result is a relatively rich society, but one that is highly unequal.

Mauritius

Mauritius, which is often not thought of as an African country, is perhaps the most unusual choice. An uninhabited island before Dutch colonization in the 17th century, its ethnic makeup of Indians and Creoles resembles the Caribbean more than continental Africa. Moreover, Mauritius became independent in 1968 at an income level that most contemporary Africans would envy (see chart above).

Nonetheless, Mauritius’s developmental record is impressive. Originally a sugar colony, a tax on sugar receipts was used to funnel landowners’ capital from agriculture to manufacturing. In the subsequent manufacturing drive, powered by the exports of apparel and textiles, GDP rose 6% a year. With egalitarian, broad-based growth, poverty was virtually eradicated.

However, Mauritius was unable to make the leap from garments to higher-value manufacturing, and the sector’s share of GDP has since halved from over 20 percent to just 11 percent by 2020. Alongside Seychelles, it is one of only two African countries ranked “very high” on the UN’s Human Development Index.

Rwanda

Ethiopia and Rwanda, as recent developmental darlings and conscious emulators of the East Asian example, are perhaps the least surprising inclusions in Studwell’s list.

Under President Paul Kagame, Rwanda has explicitly modeled itself after Singapore (including Lee Kuan Yew’s authoritarian tendencies). At first blush, this struck me as absurd: Singapore is an island state on the crossroads of the world’s richest sea lanes; Rwanda is a landlocked country in poor central Africa.

Studwell’s account convinced me there is an economic logic to this strategy. The high cost of road transport means that importing goods into Central Africa is prohibitively expensive. Rwanda does not necessarily need to compete with the world; by delivering on infrastructure projects and maintaining rare political stability, it can attract investment as a kind of entrepot to Africa’s Great Lakes. Under this formula (with perhaps some slight fudging of the numbers), Rwanda has maintained impressive 7% growth for the past decade.

The big question surrounding Rwanda is if the growth coalition can hold together. Nowhere else in Africa is the tragic legacy of ethnic division more apparent; the present Kagame regime took power by overthrowing the perpetrators of the infamous 1994 genocide. Rwanda’s military involvement in the Eastern Congo, which represents both a source of raw materials and a lucrative market of 30 million, adds a further dark cast to its developmental success.

Ethiopia

It is Ethiopia that comes the closest to achieving all parts of Studwell’s formula. As a country of 135 million people, it has the scale to set a major example to the world and to take a serious bite out of Africa’s poverty all on its own.

Meles Zenawi, prime minister from 1995 to 2012, was an avid student of East Asia. (His thesis outline is available online; for any economist with a wavering faith in the power of ideas, read the bibliography.) Under his leadership, the Ethiopian state invested heavily in agricultural extension and irrigation, improving the yields of smallholder farmers. It began (with Chinese support) building industrial parks to support an export manufacturing base. Most ambitious of all, it began work on the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, one of the largest hydropower projects in the world, to find a permanent solution to Ethiopia’s energy woes.

No student of How Asia Works could have done better. Had How Africa Works been published before November 2020, it’s easy to see how a celebration of Ethiopia might have occupied most of the book.

But the outbreak of civil war derailed Ethiopia’s progress, and demonstrated the continuing risk of ethnic conflict to the prospects of economic growth.

Mashamba Na Viwanda

Unlike East Asia, Africa has no unqualified economic miracles to point to. The result is a book that is more diffuse in its rhetorical impact than How Asia Works, but also one that is perhaps more realistic about the constraints. Some of the swaggering confidence that marked the Asian Triple Growth Formula is gone.

Nonetheless, Studwell insists that universal prescriptions still exist:

… despite the radically different context, I have found that the policies that were most effective in East Asia in producing economic transformation are the same ones that have worked in the handful of cases of early success in Africa. In this respect, there is no African exceptionalism.

As a recap, these policies were smallholder agriculture with state support, industrial policy to support export-led manufacturing, and tight government control of finance to support all these aims. To these three, Studwell adds the extra ingredient of a “developmental political coalition”—taken largely for granted in the relatively homogenous, authoritarian states of East Asia, but far from table stakes in ethnically fractious, democratic Africa.

I’m no expert on any of the four countries Studwell discussed. But let me comment on two of Studwell’s key pillars from an economic lens: agriculture and manufacturing.

Agriculture

Like in How Asia Works, Studwell advocates for smallholder farming in Africa, citing the familiar evidence that small farms grow more crops per acre than big ones. (In jargon, this is the “inverse farm size - yield relationship”.) In theory, then, redistributing land from big landowners to smallholders should improve aggregate productivity.

Smallholder farming may be desirable for political, distributional, or social reasons. In most societies, owning your own plot of land naturally has enormous psychological value. In Kenya, for instance, having a rural shamba is a source of social status and, in urban downturns, acts as a form of social insurance. Regimes that ignore this basic fact invite unrest: the anti-communist regimes of East Asia likely had to do some form of land redistribution or risk being thrown into the sea.

But on the narrow point of efficiency I am more agnostic. I mentioned earlier my complex relationship with How Asia Works; my academic work finds that the major land distributions in Taiwan and Mainland China had smaller yield effects than previously thought. Having pondered this question for years, it now seems to me simplistic to expect there to be a universal Platonic relationship where the smaller the farm, the higher the yields. Far more likely that this relationship depends on the crop, the soil, and the available infrastructure. Wheat yields in Europe, for instance, seem to be the highest on large farms, while rice yields in Asia can grow on tiny plots with the near-endless application of labor.

But on Studwell’s broader theme, of a renewed developmental focus on agriculture, I am in complete agreement. African smallholders, ignored by their states and deprived of support, are struggling. According to the best available data, stretching from 2008 to 2019, both smallholder yields and total factor productivity have been declining by around 3 to 4% a year.1 It’s difficult to envision lifting 460 million Africans out of extreme poverty without improving the meager returns from their primary occupation.

Manufacturing

The other noteworthy component of the Studwellian recipe is a heavy emphasis on growing manufacturing, fostered by state industrial policy.

What’s so special about manufacturing? Studwell leans heavily on an influential 2013 paper by Dani Rodrik, who argues that manufacturing possesses the unique property of “unconditional convergence”. Unlike other sectors, manufacturing in developing countries appears to catch up quickly to the global frontier of productivity. Intuitively, because most manufactured goods are tradable, manufacturing firms are more exposed to the pressure of international competition, forcing them to innovate; moreover, manufacturing processes (compared to, say, crop growing practices) are readily transferrable across borders.

I was long a True Believer in this thesis, but have recently had my faith shaken. New empirical work, forthcoming in the American Economic Review: Insights, suggests that unconditional convergence in manufacturing may partly have been an illusion of the data. (In that paper, somewhat cheekily, it turns out that agriculture and services display convergence, but manufacturing does not.)

Of course, no one’s worldview is really determined by a paper based on a few cross-country regressions. (Even one by Dani Rodrik.) What convinces most is how central manufacturing was to the East Asian miracle, still the only region of the world to ride the escalator up from poverty to riches.

This relates to a deeper problem with the prospects for African industrialization: namely, that industrialization never happens in a vacuum. A successful domestic manufacturing base is a product not only of your own industrial policy, but global market conditions and the strength of your competitors.

One obvious risk is automation, which threatens the manufacturing sector’s absorption of labor, and may help keep Chinese factories globally competitive despite rising wages. Studwell quickly brushes off these concerns (“[the] labour cost in a country like Madagascar is US$65 a month… the cost of an advanced industrial robot in the apparel sector is over US$100,000”). In my view they deserve deeper inspection.

Moreover, even if Studwell’s right, Africa has strong competitors in the race to claim China’s manufacturing share: South and Southeast Asia, with their large urban populations and increasingly capable states. Studwell notes optimistically that Africa has finally caught up to the educational attainment of East Asia in 1960; he fails to note that South and Southeast Asia have long exceeded that level.

A Bias For Hope

Longtime readers of Studwell’s writing—from 2003’s The China Dream to 2013’s How Asia Works to the present volume—will know that he has a strong contrarian streak. The China Dream was notably downbeat about China’s development prospects just as the largest export boom in history was getting started (p. xii: “the economic foundations of contemporary China have been laid on sand and [are] constructed from the kind of hubris that drove the Soviet Union in the 1950s”). How Asia Works was stridently dirigiste, right at the high-water mark of the Neoliberal Age.

By contrast, Studwell sounds unusually optimistic about Africa, where, post-aid cuts, the pendulum of international opinion has swung decisively towards gloom. State-led improvements in health and (to a lesser extent) education, supported in part by international aid, have eroded some of Africa’s historical disadvantages. Most of all, the demographic boon of the world’s youngest population will give growth efforts a brief but powerful tailwind.

As an analysis of what makes countries grow, the Studwellian formula is of course incomplete—but, with 54 countries and 1.6 billion people, how could it not be? What makes Studwell nonetheless compelling to read is his steadfast underlying belief that poverty is a product of policy decisions. Analytically, this is of course not quite right: as the first part discussed, strong historical and geographic factors condition what’s possible. But, for a practitioner, such belief—what Albert Hirschman once called a bias for hope—is surely a necessary condition for action.

Development is ultimately an act of imagination, of envisioning what’s not yet there. Sound policy requires that these visions be supported by durable political coalitions and within states’ capabilities. (A latent motif of the book is eager states overreaching with megaprojects, in a vain attempt to leapfrog their peers.) But even the mixed success of import substitution industrialization or the follies of incomplete irrigation megaworks seem preferable to the status quo of seeking rents while sitting on one’s hands.

On one final point I am in wholehearted agreement.

At various points Studwell discusses “demonstration effects”: the positive influence one country can have on peer states. Demonstration effects are essentially impossible to falsify in the modern language of econometrics, but are unmistakeable in the real world. (If you disagree, take a look again at Meles Zenawi’s library.) The world really only has two industrial clusters: one began in 18th century Britain, and grew to encompass most of Europe and its colonial offshoots; the other started in Meiji Japan and spread to the rest of East Asia. In both cases, culturally similar neighbors saw what was possible and copied the recipe.

In one sense, this is a note for pessimism. If history is any guide, the great global factory complex will first stretch down from China through to mainland Southeast Asia and Indonesia, and westward through Bangladesh and India, long before it ever reaches Africa. But in another, it sounds a note of hope. If even one African country manages to sustain the kind of broad-based growth that Studwell describes, it could do for its neighbors what Meiji Japan accomplished for the rest of Asia. It may only take one resounding success to shatter the illusion—fed by sixty years of disappointment, egged on by lingering prejudice—that Africans are incapable of achieving economic prosperity.

Studwell presents a careful and sensitive discussion about the tradeoffs between formal land rights (which would make possible land reform) and the present communal landholding that dominates the continent. Considering the elite capture of legal systems, which will likely only favor rich landholders, he ultimately decides that communal landholding is likely better than the alternatives. Smallholder agriculture will have to wait.

Thanks for the review I cant wait to get the book myself, but my issue is if these are the four examples, there's plenty to leave desired.

1) I am glad he mentioned Mauritius. Its a great study on manufacturing and I am glad he mentioned ethiopia on farming, great examples.

2) Botswana's success is less of institutions and more of the fact that it maintained its joint venture with de beers instead of nationalizing diamonds like Sierra Leone. De beers had a global monopoly until the US DOJ anti trust case in the 2000s. So unlike the rest of africa which had commodity prices busts in the 1980s and 1990s, botswana due to its dependence on the De Beers diamond cartel, was able to hoard diamonds to prevent a price bust collapse.

But now that de Beers lost its monopoly power and that synethetic diamonds from india and china have flooded the market, botswana is struggling now. Also botswana has tried to diversify to manufacturing many times, but south africa has sabotaged botswana's manufacturing capabilities with import quotas in their customs union. They also have some structural problems for manufacturing. Its certainly a success story by african standards, but with an asterisk.

3) You mentioned rwanda with minerals in congo so i wont continue on that. I hope he delved into how rwanda basically has a party-military fusion economy similar to taiwan back in the day.

But even then, Rwanda is still poorer than half of sub-saharan africa. Its per capita incomes matches its neighbors uganda which has 4x its population.

Its a little weird to use rwanda as an example when its still playing catch up growth with the rest of the continent post genocide.

Great review, thanks!