Indonesia Climbs the Chain

Nickel, Industrial Policy, and Poverty Reduction

The “Global Value Chain” is now an exhausted metaphor, but it’s worth reminding ourselves now and then what it means in human terms.

At the bottom are the raw materials producers, among them the child slaves in the Congo digging out cobalt with their bare hands. Somewhere in the middle are the gray towns like Luoyang and Dongguan where ores are melted down and workers put their byproducts into little cases to be shipped abroad. Then at the top are the people like you and me, clacking away at the machines with cobalt-cathodes humming inside, who are so inconceivably productive we can spend most our days Just Reaching Out and Circling Back and Following Up Again.

In our world, we know of no escape from poverty other than climbing the value chain. And perhaps the boldest attempt in recent memory is Indonesia’s gamble on nickel.

If I Had a Nickel Every Time Said Industrial Policy

Nickel is a key component in the lithium-ion batteries used by electric vehicles (EVs). With global EV sales surging amid the global green transition—17 million were sold in 2024, a 25% increase over 2023—nickel has become a critical link in the global value chain.

Indonesia mined around 1.8 million tons of nickel in 2023, more than any other country, and nearly half of global production. But for decades, it has been stuck at the bottom of the value chain. Raw Indonesian ores (saprolite and limonite) were sent abroad, largely to China, where they were smelted, processed, refined, and manufactured into higher-value goods like batteries and stainless steel, fetching higher-value prices.

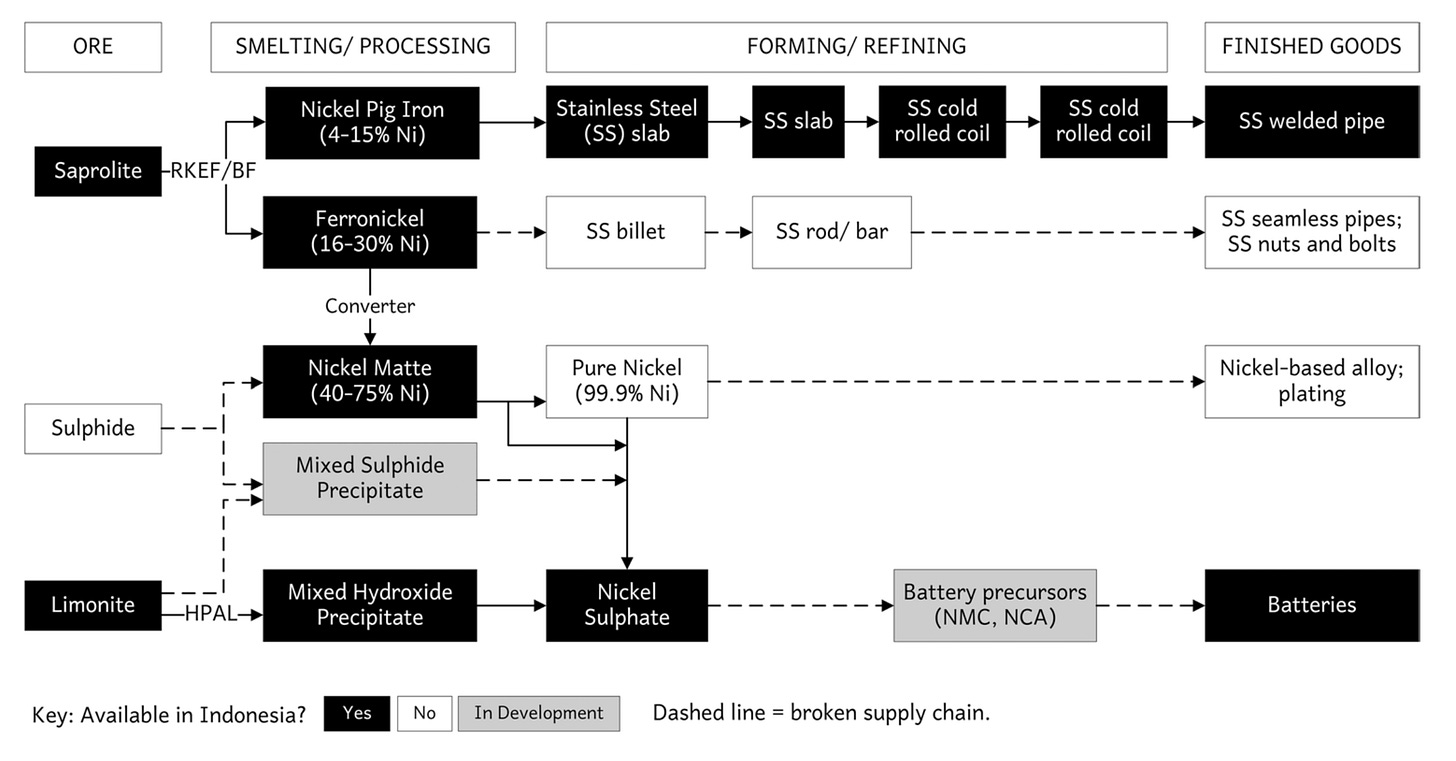

The chart below, from Wijaya and Jones (2024)’s excellent analysis of the geopolitics of Indonesia’s nickel industry, shows just how many stages follow mining nickel from the earth:

For many developing countries, extracting rents from raw minerals is the full extent of their policy ambition. But, over the past few decades, Indonesian policymakers have tried to leverage their commanding market position to begin a slow, tentative ascent up the chain.

Starting in 2009, foreign-owned mining firms were required to divest up to 51% of their ownership to domestic firms. In 2014, a ban on the export of nickel ore went into effect, excepting some low concentrations. And in 2020, under President Jokowi, the export of all unprocessed nickel ore was banned outright. At the same time, Indonesia has doggedly courted foreign capital, attracting around $30 billion in investment by 2023 to help build nickel processing factories.

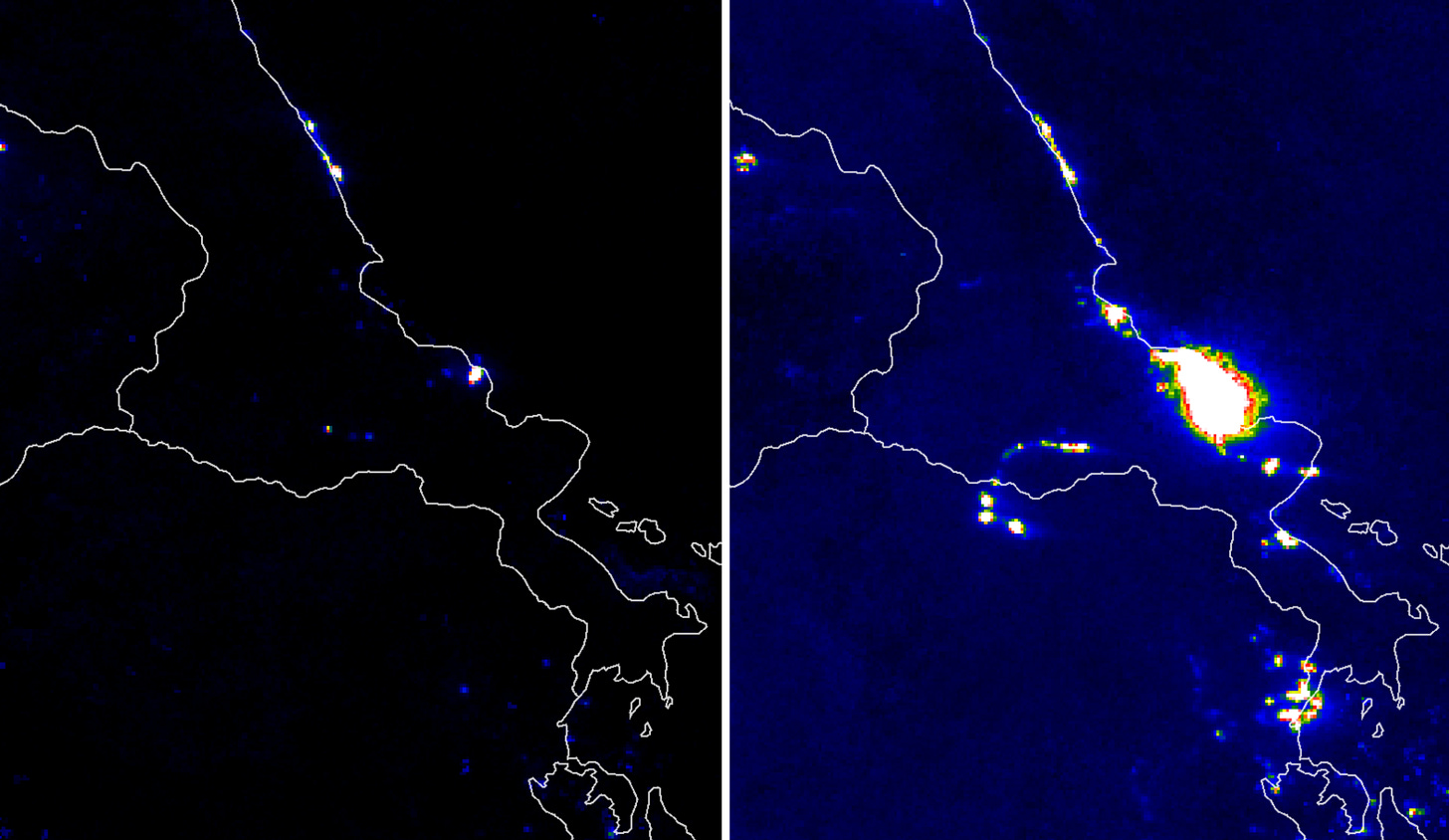

Central Sulawesi—along with Halmahera Island, home of the majority of Indonesia’s nickel deposits—has received around $7.5 billion in foreign direct investment, the lion’s share of which is from Chinese firms. Likely the largest investment is the 10,000-acre Morowali Industrial Park in central Sulawesi ( red), which processes the ores right by where it is mined:

The massive growth of the Morowali complex can be easily seen from space, as shown below in night-time satellites between 2014 (left) and 2023 (right):

Indonesia’s Gambit

Thus far, Indonesia’s gambit has paid off handsomely. Processed nickel have grown to be almost 10% of exports as of 2023, and Indonesia has become the largest exporter of stainless steel in the world.

In 2019, the European Union raised a complaint under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), arguing that Indonesia’s export restrictions were were inconsistent. Indonesia appealed in 2022; the dispute has been stuck in limbo due to vacancies on the World Trade Organization’s Appellate Body.

Yet Indonesian leadership remains proudly defiant. Here’s Muhammad Lutfi, Minister of Trade under Jokowi, at Davos 2022. It’s worth listening in full as it lays bare the power dynamics of global trade:

Journalist: Mr. Lutfi, you wanted to triple your economy by 2030. That is a lot of consumption and a huge amount of demand. Is the world geared to support your growth ambitions?

Mr. Lutfi: Well, I don't know about the world, but I want to continue what the minister from Peru says. If we just rely on selling a basic commodity, the country cannot sustain [itself], I guarantee you that. But I want to tell you a story. I don't want to name the commodity, but we stopped the export of one particular commodity. [Ed.: this is, of course, nickel.] We got about $1.1 billion in 2019 selling that commodity. We stopped it and forced people to make value additions to that. We created stainless steel. Suddenly, Indonesia became the number two stainless steel producer in the world.

Do you know how much the multiplication is? 10.86 billion dollars that very year after. Double that in 2021 to be $21 billion. This year it will be 10% of Indonesian exports coming from stainless steel. The recipe is value added, but like my friend says, when a developing country creates something, the developed countries are not happy. So right now, I'm having dispute settlements with the developed countries almost like every other day, but for Indonesia we have no other choice but to fight it.

[The exchange continues with some pointed questions from the Davos interview about resource nationalism.]

Pause for a moment and consider the position of asking someone from a country with less than $5,000 in GDP per capita, where around half the population lives on less than $3.65 PPP a day, if the world is ready for its “growth ambitions”. Should poor countries wait to ask for permission to start growing?

But Western skepticism of Indonesia’s nickel push is less rare than you might think. You can detect a similar tone from this major 2023 photo feature by the New York Times, which examined the dark side of the nickel boom on Sulawesi:

[Mr. Jamal] and his family complain about the dust pouring off piles of waste, the belching smokestacks, and trucks rumbling past at all hours bearing fresh ore. On the worst days, residents don masks and struggle to breathe. People go to clinics with lung problems.

“What can we do?” Mr. Jamal said. “The air is not good, but we have better living standards.”

Here is the crux of the deal that Indonesian officials have cut with deep-pocketed Chinese companies now dominating the nickel industry: pollution and social strife in exchange for upward mobility.

What Mr. Jamal and his community have had to endure is appalling. But I have to admit, somewhat sheepishly, that my first thought was how the Times’s account smacked of typical privileged Western handwringing about industrialization, when the alternative is brutal poverty. The transition to factory work is never a cakewalk—but here is a case of a poor country trying to wield the tools of industrial policy, however imperfectly, to climb from the lowest place in the value chain. If it succeeds, there is perhaps no better blueprint for other resource exporters looking to do the same. Who are we to dismiss it?

Where’s the Beef [Rendang]?

But my second reaction was to suspend judgment. Is it actually true that nickel mining has relieved poverty?

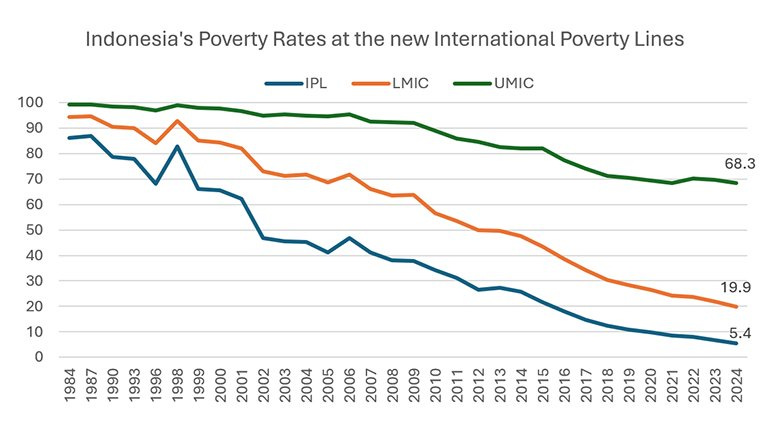

At the national level, Indonesia has taken significant economic strides, averaging around 5% growth in real GDP and around 3% in per capita terms in recent years. By basically every international standard, poverty has fallen:

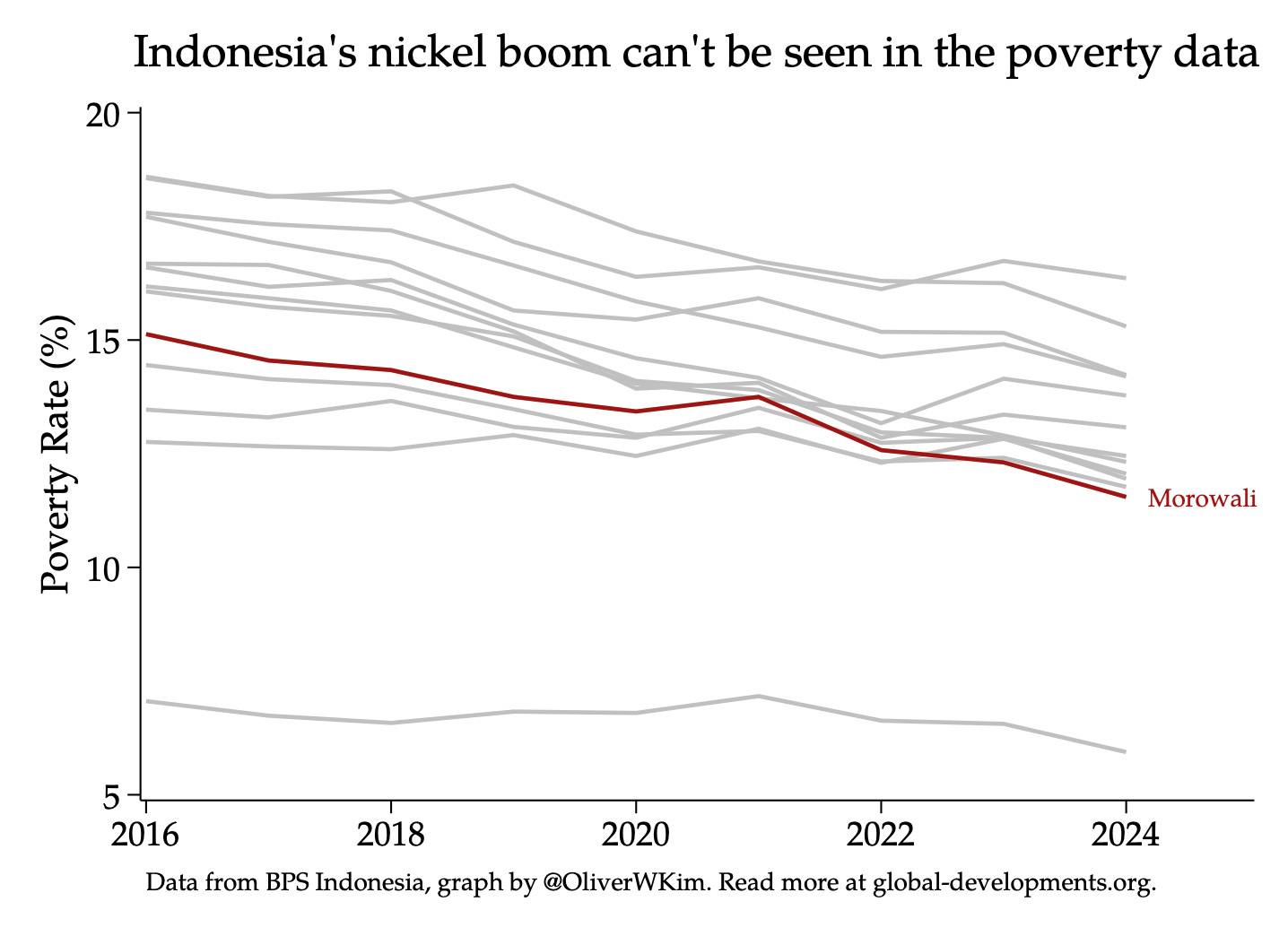

But what has it meant for Sulawesi? The chart below shows poverty rates across regencies in Indonesia, with Morowali Regency—the home of the Morowali Industrial Park—highlighted in red:1

Morowali’s poverty rate has seen a modest decline since 2016, from around 15% to 12%, but this puts it squarely in the middle of the pack of other Sulawesi districts—and not far from the decline in the national average, which fell from 10.9% to 8.6% over the same period. When set against the threefold increase in Indonesia’s nickel export value, it’s tiny.

This is not a new finding: a 2024 report by the Lowy Institute also found limited poverty reduction in the Konawe district, home of a major nickel smelter, despite significant local economic growth. But the enormous growth of the industrial parks—Morowali Industrial Park alone employs 38,000 workers, 6,000 of them Chinese—have hardly moved the needle on local poverty.

Nickel has likely been a boon to the broader Indonesian economy, and perhaps areas outside Sulawesi; its precise effects are hard to identify. But it has almost surely benefitted Indonesia’s business elites. Members of President Jokowi’s inner circle have developed mining and processing interests, and over half of Indonesia’s top 50 billionaires are now involved in nickel (Wijaya and Jones 2025, pg. 11). Local elites, too, have gotten in on the action, taking bribes in exchange for licenses and security. Meanwhile, nickel workers—both Chinese and Indonesian—work in dangerous conditions, with allegations of frequent accidents, withheld pay, and suppression of unions.

Critically, domestic inequality also intersects with geopolitics. Despite Indonesian attempts to hedge between the West and China, Chinese firms dominate the space. China accounts for around 90% of Indonesia’s nickel exports. Mandala (2024) estimates that around 75% of direct profits accrue to foreign—likely Chinese—shareholders, with the rest flowing to Indonesian elites. By binding together Chinese capital with Indonesian politics, the nickel industry is becoming a gravitational force in the tricky nexus of Chinese-Indonesian relations.

Kicking Away the Ladder?

With its bet on nickel, Indonesia is now the world’s industrial policy darling—it already has at least one international emulator in Zimbabwe, which banned lithium exports in 2022. After its success inching downstream, President Prabowo Subianto is now leading a new push to build a domestic electric vehicle industry. For a country that currently does little more than raw materials assembling and parts assembly, jumping to manufacturing is (needless to say) a bold leap.

I don’t want to pre-judge. But, peering past the hype around Morowali reminds us that we should be careful before assuming that industrial policy must be pro-poor. Poverty reduction is never a purely technocratic exercise, and questions about industrial policy can never be entirely divorced from those of political economy—including those of global geopolitics. Development economists do themselves an analytical disservice when they fail to ask: who gains from the present state of affairs?

It’s one thing if residents of Sulawesi like Mr. Jamal and his family have had to risk exposure to toxic pollutants in a successful escape from poverty. It’s another thing entirely if those bearing most of the burden see few of the benefits.

Poverty data from Badan Pusat Statistik (BPS). Indonesia’s poverty line is somewhat unusual: it’s the average of 67 local poverty lines, where the basket of goods changes each year. Poverty reduction is thus a moving target—not necessarily a bad thing for policymakers, but harder for an analyst to interpret.

This is a very interesting and balanced article. I am not surprised to learn about the benefits to a small elite. Bur I think the analysis of the bigger picture is incomplete. If exports of nickel, or stainless steel, or whatever are to shift the national poverty dial, what matters is how big they are as a percentage of GDP. I do not know, hence I am asking you!

If foreign expertise isn't used you just have a much smaller volume of production. This is the problem with you people, you see the world as a zero sum game. You rather the poor get poorer than the rich get richer.