No, South Korea Was Not Poorer Than Kenya in 1960

With A Personal Coda

Sixty years ago, East Asia and Africa were both desperately poor. Then East Asia experienced a miracle and Africa didn’t. Why?

The space is now open for the author to offer their favored explanation, which (logically) occurred in the past sixty years.1

Here’s a recent example:

The Taiwanese miracle ranks among the most dramatic examples of modern economic development. In 1950, Taiwan was a poor, primarily agrarian economy, with a real GDP per capita lower than Ghana or Afghanistan. Today, after 50 years of over 5% growth in GDP per capita, it is a manufacturing powerhouse with living standards comparable to France or Germany.

The author, of course, was me, in a coauthored paper with Jen Kuan Wang on Taiwan’s 1950s land reform. Mea culpa! We’ve since revised it. But far more important people than me have tried this sleight of hand. Here’s a 2021 quote from Uhuru Kenyatta, when he was President of Kenya:

If the Asian Tigers were at the same level of development as Kenya in 1963 and Kenya actually lent South Korea some money to implement its development plan in 1963, the question is what happened? Why were we unable to develop as fast as they did?

If Kenyan presidents are getting in on the action, it’s time for some good old-fashioned economic history myth-busting. Was South Korea really poorer than Kenya at independence?

It’s a simple question, but doggedly following the thread leads us quickly down the rabbit-hole of economic history—and, for me, some personal history as well.

A Brief Education

Let me start off with a confession: I lied. It is literally true in the data that Kenya had a higher GDP per capita than South Korea in 1960. Here’s real GDP per capita from the Penn World Tables:

While heeding all the warnings from a few weeks back about not taking any of these GDP estimates too seriously, it’s clear that up until around 1970, South Korean and Kenyan income levels were at least in the same ballpark.

But there are enormous historical differences hidden behind these GDP figures.

Consider education. At independence, South Korea and Taiwan had far higher rates of primary education than most of Sub-Saharan Africa. We can see this in a plot of countries’ 1960 GDPs against their primary school completion rates (with the word of caution that the data is likely not very good):

South Korea and Taiwan (red) had unusually high levels of primary education for their relatively low levels of GDP—over 30% of people completed primary school, at annual incomes of just $1224 for Korea and $2553 for Taiwan. By contrast, most African states (blue) had lower educational endowments than their incomes might imply, falling below the line of best fit. In the Barro and Lee data, only one country, Senegal, had a primary school completion rate over 20%. Kenya was at just under 9%—less than a third of Korea or Taiwan.

Secondary and tertiary (university) schooling were also relatively common in Korea and Taiwan, and rare in Sub-Saharan Africa:

Why does education matter for development? It almost feels ridiculous to type out that sentence—education is a good in itself—but it’s worth a standing-on-one-foot recap of the economics.

The first, obvious answer is that education creates better workers. At a minimum, knowing how to read and write and add and subtract makes you more productive. During the second half of the twentieth century, East Asia’s combination of a relatively productive workforce with low levels of wages turned out to be economic dynamite. As the West grew richer and shifted into services, a channel opened up for cheaper foreign manufacturers—and capital chose to go where labor was cheap, pliant, and productive.2 As the East Asian economies rose, they needed educated engineers, inventors, entrepreneurs, etc. to do the engineering, inventing, entrepreneuring, and et cetering—which the educational system duly supplied.

By contrast, in Africa, skilled labor was often in short supply. In 1964, only 53% of Kenyan administrative, executive, and managerial positions were held by Africans. Even in 1963-66, only 38 out of 98 graduates of University College, Nairobi were African (the vast majority were Kenyan Asians). As a settler-colony, Kenya actually had a relatively high level of colonial investment; in the most infamous case, at independence the Belgians left only 30 people in the Democratic Republic of the Congo with two years of schooling at the university level.

One Level Deeper: State Capacity

The second, more subtle channel for education’s importance is its relationship with state capacity. Here, cause and effect are also intermingled: you ideally want well-trained people to manage your government, but high rates of education are as much the products of effective states as they are its inputs.

Catch-up growth in the 20th century was almost entirely state-led. The South Korean and Taiwanese states intervened extensively in markets, promoting agricultural extension, fostering new industries, and sending bureaucrats abroad to ply their country’s wares. When they pursued these policies, they could draw from a deep well of former bureaucrats trained by the Japanese colonial state. According to Atul Kohli, “there were 40,000 Koreans qualified as government officials on the eve of the second world war”.3 Koreans were barred from the higher levels of government—in the Japanese empire, as elsewhere, colonialism was not intended to benefit the colonized—but at independence there was a relatively large stock of administrators with at least some government experience.

The Japanese empire reached far deeper into its colonies than any European empire ever did in Sub-Saharan Africa. In 1941, there were more than 60,000 police in Korea, or 2 for every 1000 people; at the end of World War II, there were roughly 5,000 police in Kenya, or 1 for every 1000. As a settler colony, Kenya was again relatively well-policed; in the extreme, British Nyasaland (now Malawi) had just 500 police in 1945 for an estimated population of 2 million—a ratio of 0.2 per 1000.

It’s important to remember that colonial police were, first and foremost, tools of coercion and control. In Korea, they committed hideous abuses of power, including sexually enslaving comfort women and trying to stamp out the Korean language and culture. Nor did the relative scarcity of the state preempt colonial cruelty in Africa, from the Belgian atrocities in the Congo to the British concentration camps in Kenya. Nothing says that police states should be developmental—but in the history of statehood, gendarmes have usually come before teachers and doctors. If the police are the knife’s edge of the state, the blade did not penetrate deeply. The European imperialists in Africa tried to do “administration on the cheap”—and the newly independent African states inherited the result.4

To be clear, I am not saying that well-educated bureaucrats were the only things separating effective Asian states from ineffective African ones. (I’ll go into some of these deeper differences in a moment.) Nor is it to say that newly independent Africa did not have first-rate administrators—for instance, under the skillful leadership of Charles Karanja, Kenya’s Tea Development Authority made the country the second-largest tea exporter in the world.

But these were the exceptions to the rule. The fact remains that without a stock of capable administrators, industrial policy and export targeting and infrastructure-building—or even Adam Smith’s minimum of “peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice”—are a nonstarter. And regardless of your theory of development, 30 university graduates is not the correct number.

It’s Deep Roots All The Way Down

Let me go just one level deeper. Surely some substantial chunk of state capacity had to do with pre-colonial state capacities. Japan’s colonial project in Korea lasted around forty years; British rule in Kenya lasted for just sixty. In each case, the colonial regime had to build atop of—and confront—indigenous political institutions that had existed for far longer. (This explains why the Japanese needed so many police.)

In East Asia, colonization confronted some of the oldest states in the world. China of course was the forerunner, but by AD 400-800 Korea and Japan had formed cohesive states, with clear territorial boundaries and sophisticated administrative capacities. To give one striking data point: in the 16th century, East Asian armies were fielding thousands of well-drilled musketeers, decades before the practice caught on in Europe.5

Precisely how much the ancient continuity of East Asian states matters for development is still a little murky, and the delineation with colonial legacies is still an area of active debate—but the balance of evidence suggests that the legacies of these pre-colonial states stretched through the colonial period, extending even into the post-independence era. For example, places in Korea with more Joseon-era civil service exam passers saw higher levels of education during the colonial era, and areas in Vietnam governed by the Confucian Dai Viet state have higher modern household consumption.

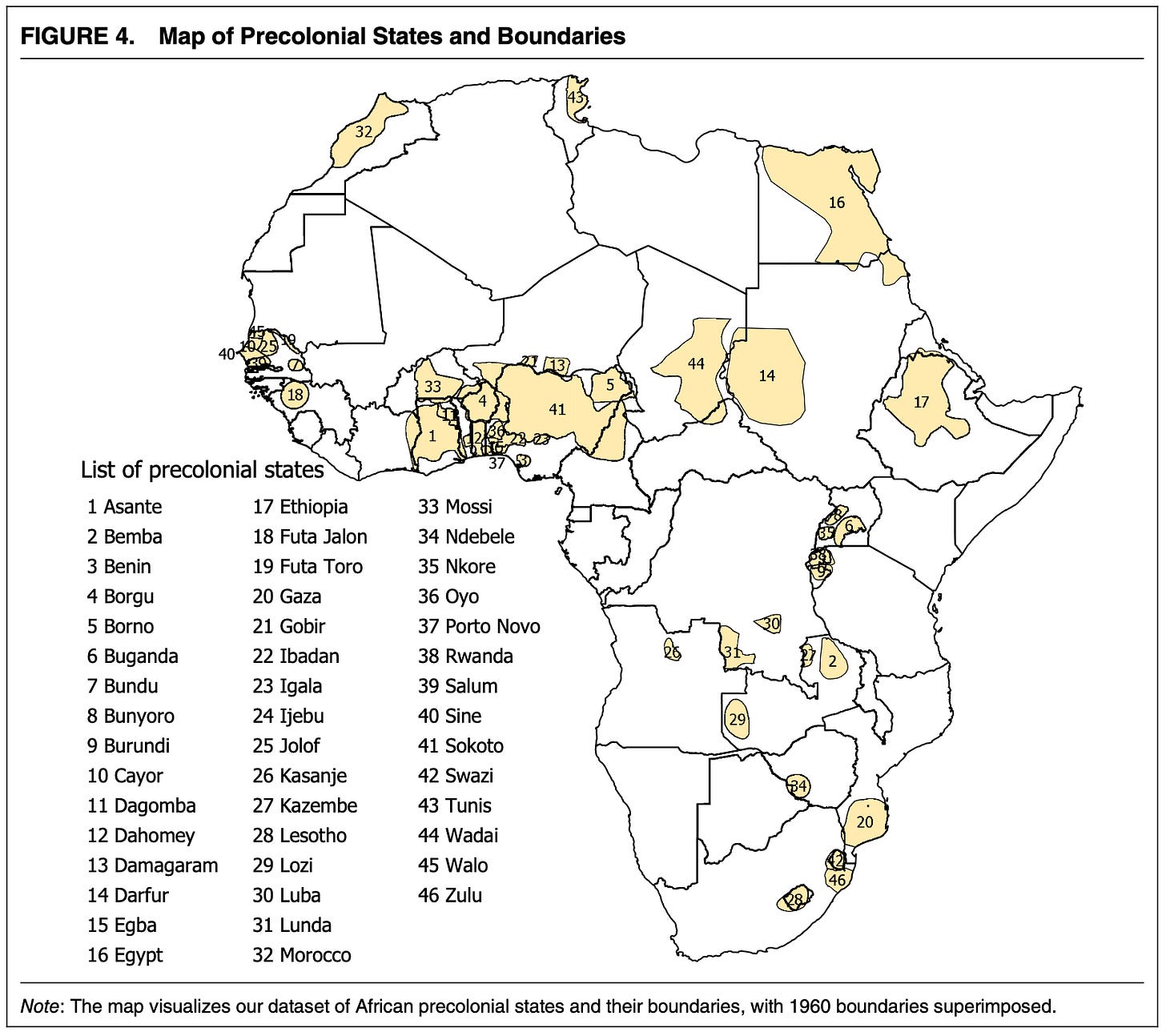

By contrast, before colonization, in large parts of Africa, people lived outside of state-level units, as illustrated by this map by Jack Paine, Xiaoyan Qiu, and Joan Ricart-Huguet (2024):

The relative absence of pre-colonial states meant that the newly independent African states were largely European inventions; modern Kenya, for instance, inherits the boundaries of British East Africa, which was created by pulling together the Kikuyu, Luo, Luhya, Kalenjin, and Kamba ethnic groups. Paine, Qiu, and Ricart-Huguet have shown that colonial boundaries followed the frontiers of pre-colonial states more than once thought—but they could still stir conflict by lumping together disparate ethnic groups, and encasing them in newly invented units. Moreover, colonial policies often worked to exacerbate and accentuate these ethnic distinctions, making ethnic tensions not a bug, but a feature. Africa’s long history of civil wars and ethnic conflict are their tragic legacy.

I’ve just written several hundred words on how central states are to development, so allow me to briefly subvert my main point. It’s important to not succumb entirely to the Eurocentric trap that Africa before colonization was a static, stagnant monolith because of its lack of states. African states formed where it was rational to do so, in places like the Ethiopian highlands where population density was high and the disease burden was relatively low.6 Otherwise, decentralized gerontocratic or democratic systems of governance often suited local conditions better. Moreover, the best available guesswork by Broadberry and Gardner estimates incomes in parts of Africa were likely above subsistence levels at the beginning of large-scale colonization, suggesting that some societies may have already departed from a Malthusian economic regime.

Nonetheless, to the extent that states were the vehicles of rapid development in the 20th century, the newly independent African states were dealt a bad hand. While Korean nation-builders could rely on hundreds of years of shared statehood, Kenya’s founding fathers had to build atop states with far less internal coherency—while starting out with a shallower pool of educated personnel.

This is not to say that post-1960 policies didn’t matter for the economic divergence of East Asia from Africa, and everything was pre-ordained. Nor is this an argument that education and state capacity are all that matters; I’ve ignored gender, religion, culture, the international environment, and probably a half-dozen major research literatures who are all furiously typing away in the comments. But even through this relatively narrow lens, it’s hopefully self-evident that there’s a fundamental shallowness to pulling a GDP estimate, and assuming that it tells you all there is to know about a country’s development potential.

A Personal Coda

Having fallen into the East Asia - Africa Trap before, I can tell you precisely why so many people make this mistake. Simply put, it is rhetorically useful to emphasize that countries can alter their economic destinies. The growth South Korea saw over the past hundred years is almost inconceivable—and if Korea could transform itself, why not Kenya? Emphasizing agency and the possibility of radical transformation is at least a refreshing antidote to the fracasomania that can often set in in development circles.

But the temptation to juxtapose Korea and Africa also has, for me, a personal dimension.

I’m Korean-American-Canadian, by way of Hong Kong and Singapore, but my Mom grew up partly in Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Her father, my grandfather, was a career diplomat for the South Korean government. Much of the Sixties and Seventies was spent shuttling back and forth between Seoul and Paris, until at last the family landed in Kinshasa, where my grandfather was appointed South Korea’s Ambassador to Zaire, then ruled by the murderous Mobutu Sese Seko.

By the children’s accounts it was a happy time: unsupervised, free. They went to a French lycée in Kinshasa, surrounded by the remaining colonialists, largely unaware of what was going on outside of their diplomatic bubble. (A rare sign of trouble was when a child snatched my mother’s necklace in a crowded marketplace.) I would happily wager that they were the only Koreans in town—save, of course, for the North Koreans, who would occasionally drive by to shake their fists at my uncle playing Cowboys and Indians in the yard.

At the time, neither Korea was represented in the United Nations. Both North and South were engaged in a mini Great Game for recognition, sending diplomats like my grandfather canvassing across Africa. In cables from the archives, my grandfather can be spotted in Chad in 1974, delivering a donation of 10,000 vaccines in response to a cholera outbreak. A week later, he can be seen fleeing Benin after a pro-Kim Il Sung editorial appeared in the Daho Express.

I have to admit that the image of besuited Korean diplomats chasing each other across Africa is now faintly funny. What could South Korea (1980 GDP: $5097 in 2017 USD) and Zaire (1980 GDP: $2219) possibly have to talk about? But members of my grandparents’ generation had seen their country come within a hair’s breadth of destruction; diplomacy was serious business.

My grandfather, Kee Heum Shin, was born in 1928 in what is now North Korea. He must have been forced to learn Japanese in school, though I never heard him speak it. At independence, his family joined the exodus of Christians and former landowners fleeing south. Because he was lucky enough to know some English, he served out the war far to the south, as a translator at an American air force base. In the crushing poverty after the war, he served as the main support in a family of three boys and three girls. He studied hard, and went on to a promising career in Korea’s diplomatic service—to postings in France, Morocco, Zaire, Nigeria, and perhaps others I have not heard of.

To be frank, diplomacy was probably never his strong suit. As a father and a husband, tact was certainly not a quality he was known for. When he was Ambassador to Nigeria in the early 80s, he fell afoul of Chun Doo-hwan’s all-powerful KCIA, which led to the family’s emigration to the United States. That was alright, because money was his real passion. In America, he found a second wind as a liquor store owner, plowing the earnings obsessively into the stock market. Even as his health failed, and his interest in all else faded, he would get up early every morning to watch the little Tesla and Apple sparklines tick up.

Later in life, he confessed that he should have always been an economist. (Our sole economic debate occurred when I confessed, to his great disappointment, that I was a Keynesian.) A large part of this, I’m sure, was his love of money talking. But there was something else.

As diplomats, my grandparents spent most of their adult lives abroad. The family they built would spread across three continents, where if everyone was together the dinner-table talk would mingle into a creole of Korean, French, and English. (It was only a few years ago when I realized that dejeuner was not a Korean word.) The Korea they mostly knew had been bombed to ruins. One in ten people were dead. Despite all the data I showed, for the people who lived it there were few inklings of the remarkable transformation that was to come. They were frankly eager to get out.

As a child at my grandparents’ house in Washington DC, the nightly ritual was to put in a videotape we would rent from the Korean grocer. The soap operas were always a week or two behind what was being shown in Korea, but my grandparents would follow the plot-lines religiously, as closely as they watched KBS news immediately after (when, bored, I would trundle off to bed). Each year, the quality of the productions seemed to improve: the budgets got larger, the sets more ornate. Even the actors and actresses seemed to get prettier, their jawlines shrinking, their eyes widening inconceivably.

I didn’t realize it then, but some of my happiest childhood memories were sitting with my grandparents, as they watched the country they once knew transform beyond all recognition.

My grandfather passed away on Sunday, at the age of 96.

This line of thought was spurred by this tweet from the political scientist Ken Opalo, who writes the excellent Substack An Africanist Perspective.

The pliancy of East Asian labor was a product of historical contingency; I’ve written elsewhere about Lee Kuan Yew’s smashing of the labor unions in Singapore.

Kohli, Atul. State-Directed Development: Political Power and Industrialization in the Global Periphery. Cambridge University Press; 2004. p. 35.

Herbst, Jeffrey. States and Power in Africa: Comparative Lessons in Authority and Control. Princeton University Press; 2000. p. 73.

Andrade, Tonio. The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History; 2016. p. 166-187.

Nathan Nunn’s research, in part coauthored with Leonard Wantchekon, also suggests that the slave trades contributed to the deterioration of political institutions in Africa.

This is a lovely tribute to your grandfather.

However, because I am who I am, I am going to note that education is not destiny; I buy the pre-colonial state capacity argument more than education.

Let us consider the former Soviet Union as an example. Kyrgyzstan had no pre-colonial state to speak of, but has high education levels (about 30% of adults have a university degree: https://tradingeconomics.com/kyrgyzstan/uis-percentage-of-population-age-25-with-at-least-completed-post-secondary-education-isced-4-or-higher-female-wb-data.html). Its GDP/capita ($1969) looks much more like Kenya ($1949; 3.5% of the population with a university degree: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1135785/university-enrollment-in-kenya/#:~:text=The%20most%20recent%20census%20conducted,educational%20level%20completed%20in%202019.) than slightly-less-educated Georgia (GDP/capita $8120).

Indeed, in global context, all of the post-Soviet states had high overall education levels, but development outcomes have... varied. On one hand, you have Poland (GDP/capita $22,112; also sufficiently Westernized that I saw Taylor Swift there); on the other, you have Tajikistan (GDP/capita $1188). But all the post-Soviet states have relatively high levels of education. Even poor Tajikistan* has roughly the same percentage of university-educated adults as Italy (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_tertiary_education_attainment, https://www.ceicdata.com/en/tajikistan/education-statistics/tj-educational-attainment-at-least-bachelors-or-equivalent-population-25-years--cumulative-male). The difference in post-Soviet development seems to have been more about pre-USSR state capacity than (universally reasonably high) education levels.

I'd argue a sufficient supply of skilled labor is a necessary, but definitely not sufficient, condition for takeoff growth.

* yes, Tajikistan had a civil war, but so did Georgia. also, that's a low GDP/capita, even for somewhere that had a civil war.

Great post, I made a similar comparison about Ghana and South Korea.

https://open.substack.com/pub/yawboadu/p/guns-germs-and-cobalts-6th-q-and?r=garki&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

Sure the penn tables show Ghana was above, but like you said you gotta look a level deeper. I like using the comparison of Qatar vs. Singapore or Saudi Arabia vs Italy. The Arab states have higher incomes, but by looking at exports or composition of the labor force, you can tell which economy is more productive/skilled. Same issue with Kenya/Ghana vs. South Korea.

Most African economies post independence were cash crop economies in terms of exports. For Ghana at independence, over half of its exports were cocoa beans while South Korea was already selling textiles.