Quiet Americans: Research Malpractice and the Vietnam War

Land reform, economists, and the 1967 Mitchell Report

If World War II was won by the physicists, one might say that Vietnam was lost by the social scientists.1

The Vietnam War occurred as American social science was coming of age. Theories of underdevelopment and state formation and counterinsurgency were put to the test in the field—in some cases by their authors, who were now elevated to the heights of American power. Walt Rostow, one of the founders of development economics, was National Security Advisor. Robert McNamara, once the youngest assistant professor at Harvard Business School, later an influential President of the World Bank, was Secretary of Defense.

And that was just at the top. Staffing the middle levels of the Kennedy and Johnson Administrations was a cohort of young, highly-educated idealists—not unlike Alden Pyle, the title character of Graham Greene’s 1955 novel The Quiet American.

Pyle, a young Harvard grad assigned to the Economic Aid Mission, is a devotee of the fictional American theorist York Harding. He arrives in Saigon bursting with academic theories of the Third World:

“York,” Pyle said, “wrote that what the East needed was a Third Force.”

Perhaps I should have seen that fanatic gleam, the quick response to a phrase, the magic sound of figures: Fifth Column, Third Force, Seventh Day. I might have saved all of us a lot of trouble, even Pyle, if I had realised the direction of that indefatigable young brain.

And, of course, Pyle’s purpose in Vietnam turns out to be far more sinister than just foreign aid.

The role of real-life Quiet Americans in creating and prolonging the suffering of the Vietnam War—a war that killed at least a million Vietnamese and 58,000 Americans—is well-trod ground, and far too large a subject for a blog post. But the particular role of economists, and the fraught relation between research malpractice and policy, can be illuminated by a key example.

South Vietnam’s Land Question

In 1967, the Political Section of the US Embassy in Saigon commissioned the RAND Corporation to write a report on land reform in South Vietnam.

The land question lay at the heart of the Vietnam War. In 1961, around two in every five South Vietnamese was a landless peasant. In the strategically critical Mekong Delta, the situation was even worse—44% of households were entirely landless, and a further 28% depended mostly on rented land.2 Rents were onerous, often 35-40% of the total crop, leaving little afterwards to eat. The result was a society composed largely of landless peasants, with a despised absentee landlord class skimming off the top.

After Vietnam was divided in 1954, the communist North led by Ho Chi Minh enacted a popular but violent land reform, where tens of thousands of landlords were killed and their land was redistributed to their tenants. In the South, the insurgent Viet Minh, and their successors the National Liberation Front (NLF, more commonly known as the Viet Cong), similarly redistributed land in the areas under their control.

By contrast, the US-backed South Vietnamese government, led by Ngo Dinh Diem, had little interest in serious redistribution. In 1956, Diem’s kleptocratic government attempted a land reform, but it was quickly undermined by the landlord-politicians in charge—in one notable example, the minister of agrarian reform refused to give his own tenants the lower rents mandated by law.3 Over the next decade, South Vietnam made essentially no progress on land reform. In 1955, the official share of farmers that were landless was 47%; in 1966, that figure was 42%.4

Earlier in the Cold War, the United States had supported successful land reforms in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan—largely in response to earlier land redistributions in the Communist bloc (see map below).

But in South Vietnam, the US chose to ally itself with the landlords—a choice that led Diem’s advisor Wolf Ladejinsky, who had worked on the successful land reforms in Japan and Taiwan, to resign in disgust in 1961.5 Rather than promote redistribution, US agricultural policy in Vietnam restricted itself to technical fixes, like improvements to irrigation and the introduction of high-yield varieties. In fact, when government troops backed by American firepower reasserted control over rural areas, they often instituted negative land reform, reversing redistributions in areas long-governed by the Viet Minh and NLF. Contrast this with the work of the NLF, who won thousands of recruits among the millions of landless peasants with their promises of land reform—according to the American land reform advocate Roy Prosterman, a common NLF recruitment slogan was “the movement has given you land, give us your son”.6

The escalation of the war—and the failure of alternative strategies to end it—revived the land reform question in US policy circles in 1967. The US embassy in Saigon, led by the conservative Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., turned to the RAND Corporation for counsel. As a nerve center of American Cold War policy, staffed by heavyweight nuclear theorists like Albert Wohlstetter and a young Daniel Ellsberg, RAND’s report would be critical ammunition in the debate.

The job of writing the land reform study fell to one Edward Mitchell—a young economist who had just received his Oxford DPhil in 1966.

Mitchell had never been to Vietnam.

Juking the Stats: The Mitchell Report

Mitchell’s report, available here from RAND, asked the million-dollar question: what was the relationship between land inequality and insurgency? In a sense, this was an attempt to grapple empirically with a social relationship that Ho Chi Minh had intuited years ago, except using the modern statistical toolkit of American social science.

Indeed, Mitchell’s study is recognizably “modern”, intelligible to anyone who has seen some undergraduate econometrics. It centers on a single regression, estimated on 26 provinces in South Vietnam, where the main outcome is the share of hamlets that were “secure” in their level of government control in December 1964 (“C”). Mitchell regressed this outcome on six explanatory variables: the coefficient of variation—the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean—of the landholding size distribution (“CV”); the share of land operated by landowners (“OOL”); the share of farmland subject to transfer in Diem’s land reform formerly owned by the Vietnamese (“VL”); the share of farmland subject to land reform formerly owned by the French (“FL”); the share of land not covered by dense forest and hence relatively open to mobility (“M”); and population density (“PD”).

Mitchell got the following results (t-statistics in parentheses):

The key result was the relationship between government control (“C”) and the two land inequality variables: the coefficient of variation of the landholding distribution (“CV”) and the share of owner-operated land (“OOL”). Both associations seemed to point in a direction where higher inequality—a higher CV, and a lower share of land operated by its owners—was associated with a higher degree of government control. Here’s one of Mitchell’s partial scatter plots, showing the coefficient of variation against Government of Viet Nam (GVN) control, holding all other variables at their means:

Mitchell’s conclusion?

A secure province in South Vietnam is one in which few peasants operate their own land, the distribution of land holdings is unequal, no land redistribution has been carried out, large French landholdings have existed in the past, population density is high, and cross-country mobility is low.

He took this interpretation further, drawing comparisons between South Vietnam and 17th century England:

During the English Civil War, for example, the principal support for the Crown came from the north and west of England (including almost all of Wales), while the Parliamentarians were strong in most of the east and southeast… It was the better-off farmers, the yeomen, who fought for Parliament; the poorer peasants were more likely to be with the Royalists.

Based on this, and on a similar comparison with de Tocqueville’s France, Mitchell sketched out a theory of aspirations, where the poorest peasants were the least likely to dream of higher living standards and agitate for political change. In Mitchell’s eyes, the policy conclusion for South Vietnam was clear:

When this relationship exists land redistribution can be a dangerous policy from the government viewpoint.

Statistical Malpractice

Even by the statistical standards of the 1960s, other social scientists could see that the Mitchell study suffered from obvious defects. The litany of complaints raised by other scholars (starting on pg. 57) included:

A replication by another RAND economist, T. P. Schultz, using the same data made two of the main explanatory variables lose significance.

Mitchell lacked variables for Diem’s abortive 1950s land reform, which is why he used the shares of former French and Vietnamese land eligible for transfer. Substituting in the actual reported shares of lands transferred changed the coefficients.

The insurgency predictions of Mitchell’s model fared poorly out-of-sample, for any year other than 1964.

Only 26 of South Vietnam’s 43 provinces were in the sample.

Mitchell had misreported several variables as statistically significant when, upon replication, they weren’t.

The overall verdict was plain:

A majority of economists and political scientists at Rand who have carefully studied Mitchell's work believe that it cannot and should not be used to answer the five questions formulated above, because a static model consisting of a single linear equation, relating 2 to 7 variables, cannot, they feel, represent the complex political, social and military interactions that influence control in Vietnam.

But the problem was not purely statistical. Even if the statistical relationship were correctly measured, Mitchell’s causal interpretation of his results was based on a fundamental misunderstanding of the Vietnamese context.

Robert Sansom, a Rhodes Scholar, wrote a scathing critique, which was eventually published in 1971 as The Economics of Insurgency in Vietnam. Sansom, who had conducted field research in Vietnam for his dissertation, observed that the redistributions of the Viet Minh and Viet Cong were responsible for much of the measured variation in land inequality across provinces. In other words, Mitchell’s story was exactly reversed—equal areas were more equal precisely because they had been controlled by the insurgents. Sansom compared Mitchell’s mistake “to that of one who, after observing that all who had the flu had been visited by doctors, concluded that the doctors caused the flu”.7

Tony Russo, another RAND researcher who had just returned from Vietnam, took a different tack. Russo, who had been involved in interrogations of captured NLF fighters, later said: “when you’ve been to Vietnam, you know damn well that it’s the poor who are the ones who suffer more and who fight harder, who have nothing to lose.”8 In other words, a crucial variable correlated with both insurgency and inequality—income—was being omitted from the analysis. In Russo’s follow-up, controlling for income made Mitchell’s statistically significant relationship between inequality and government support disappear.

In part because of his strident critique of the Mitchell study, Russo was fired in 1968 by the head of RAND’s economics department, Charlie Wolf. His friend Daniel Ellsberg tried to reverse the decision, but failed.

The Knife’s Edge

In ordinary scholarly circumstances, Mitchell’s study should have been dead and buried. Refuted even by Mitchell’s colleagues at RAND, it showed an embarrassing lack of understanding of the reality on the ground in Vietnam.

But the Mitchell report arrived at a critical moment. In 1967, US policy towards land reform hung in the balance. As William Bredo, a project director at the Stanford Research Institute, wrote in 1970:

Throughout the period 1965 through 1968 there seemed to be sharp divisions of opinion within the GVN, the US Mission to Vietnam, AID in Washington, the State Department and the White House over what importance to place on the land reform issue. In USAID/Vietnam and CORDS it was possible to tell which view was in and which out of favor by changes in the organization and the staff assigned to the Land Reform office.

On the US side, for the most part, the forces who preferred the status quo tended to be in the ascendancy. In the GVN similar fluctuations occurred. Upsetting the political apple cart… would entail losing the political support of the landlords and their affiliates and sympathizers, the high level government officials in Saigon and the countryside, and the army officers who came largely from the landed class. It was assumed that alienation of their support would cause the Saigon Government to fall, and that the struggle against communist penetration and control in South Vietnam would fail.

In Washington, the Mitchell report found a ready audience. Despite all the objections of follow-up studies, it provided empirical verification that confirmed policymakers’ priors, slotting neatly into a theoretical consensus that supported the status quo. For instance:

In early 1967, high-level Washington officials told Robert L. Sansom, a Rhodes Scholar performing research for his doctoral dissertation at Oxford University on the economics of the Vietnamese insurgency, that a RAND study “had found that land reform was not an important source of Viet Cong support.”

According to Sansom, officials in Saigon and Washington firmly believed that “land tenure issues were not important grievances, or at least that such grievances had not served as the basis for the support gained by the Viet Cong in the areas they controlled”. In a sense, Mitchell’s 1967 study represented the high-water mark of this opposition to land reform.

The momentum finally began to shift in early 1968—but the initial impetus for change came from the South Vietnamese. In January 1968, the new President, Nguyen Van Thieu, announced a change in land policy. The existing Diem statutes would be properly enforced. Genuine land reform, in support of the people’s welfare, would become a government priority.

A few months later, in March 1968, the House’s Committee on Government Operations released a report recommending that the United States support South Vietnamese land reform. But some members on the Committee remained opposed, and filed a strongly worded dissent as a rearguard action. As a final testament to the influence of the Mitchell study, the dissenters, Representatives John S. Monagan and L. H. Fountain, cited it as evidence in their entry into the congressional record:

It can be argued that land reform is not a burning issue in South Vietnam in any event because of the sparsity of population, the steps already taken, and the ready availability of land; and there is substantial authority that supports this view. The efficiency of large tracts and the greater security which they afford in time of war, according to The Rand Corporation study for the Defense Department, have been offered as reasons why fragmentation might be questioned.

Perhaps reflecting the continued influence of these land reform skeptics, it took another two years after the House of Representatives report for land redistribution to become a reality.

On March 26, 1970, President Thieu signed the landmark Land-to-the-Tiller bill into law. Notably, it was not an American but a Vietnamese economist, Cao Van Than, who was chiefly responsible for the program’s design. Public lands would be distributed to tenants; landholdings over 15 hectares would be broken up; every household in the Mekong Delta would receive three hectares; and tenants in the Central Highlands would receive one hectare.

Fourteen years after Diem’s first abortive attempt, with hundreds of thousands dead, South Vietnam was finally attempting a serious land reform. Estimated outlays would be around $400 million, or the cost of fighting the war for five days at its height.9

Aftermath of a Study

Was the Mitchell study decisive? Did it help delay meaningful land reform for several grueling more years of war?

It is impossible to say. Perhaps another policy entrepreneur would have taken Mitchell’s place. Or perhaps the consensus in favor of doing nothing did not really need an additional study.

But the ubiquity of the Mitchell study in the history of the late 1960s land reform debate points to a great hunger among Vietnam-era policymakers for empirical verification. With numbers men like Robert McNamara and Walt Rostow at the top, data collection efforts like the Hamlet Evaluation System consumed vast amounts of blood and treasure. The Mitchell incident illustrates how a single empirical study could acquire a life of its own if it provided the results that the brass wanted to see—and even if it was refuted by a far larger body of contrary evidence.

Even if it was not decisive, the Mitchell report was an influential contribution to a machinery that called for staying the course, that said that fundamental reforms to America’s South Vietnamese client state were unnecessary, that more bombs and more men and perhaps more technical improvements to rice farming would eventually win the war—this, at a point when an additional month of fighting meant thousands of lives. 11,000 Americans died in Vietnam in 1967. Over 16,000 died in 1968. There are no precise figures for Vietnamese casualties, but in the first four months of 1967, the American bombing of North Vietnam alone was causing 3,000 casualties a month—most of which, by the CIA’s own estimates, were civilians—men, women, and children. And this is before one even begins to consider the ground war in the South.

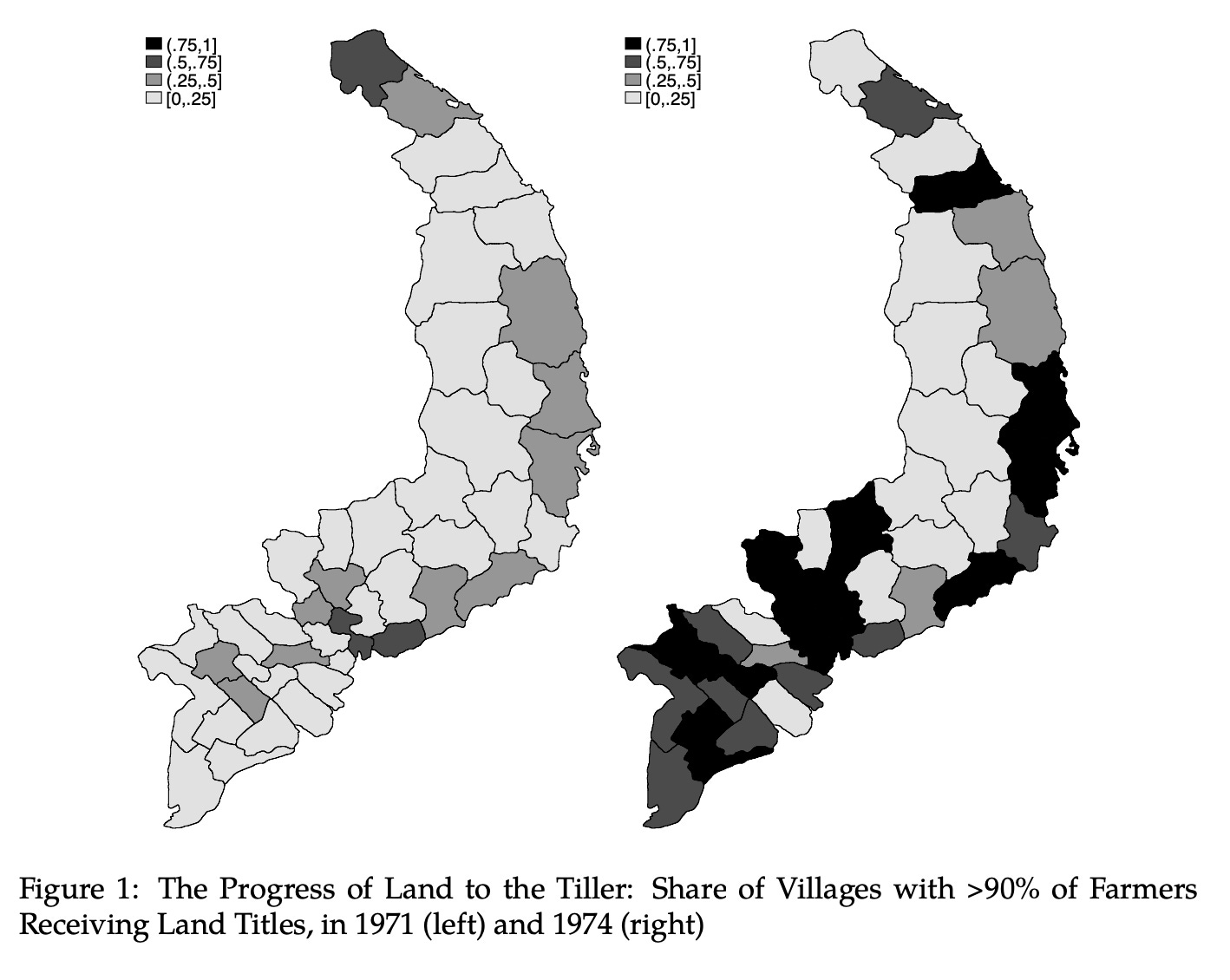

When it was finally attempted, starting in 1970, South Vietnam’s Land to the Tiller program saw some initial success. According to the last available data point, from February 1975, over 1.1 million hectares had been redistributed, representing over 45% of South Vietnam’s available farmland.

But the North’s conventional invasion in 1975 brought the experiment to a halt. Despite strong resistance in pockets, the South Vietnamese army quickly collapsed. On April 30, 1975, a North Vietnamese tank crashed through the gates of Independence Palace, marking the end of the 20-year Vietnam War. The full effects of South Vietnam’s Land to the Tiller program would never be realized.

And Mitchell?

He went on to have a distinguished career in academia. Immediately after RAND, he did a stint at the prestigious Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. From 1969 to 1972 he was a senior economist on Nixon’s Council of Economic Advisors, and in 1975, he received tenure at the University of Michigan, where he spent the bulk of his career. He retired from the university in 1988.

This formulation originally came from Robert McNamara.

Prosterman, Roy L. “Land-to-the-Tiller in South Vietnam: The Tables Turn.” Asian Survey 10, no. 8 (1970): 751–64.

Kapstein, Ethan B. Seeds of Stability: Land Reform and US Foreign Policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017. p. 148.

Callison, Charles Stuart. Land-to-the-Tiller in the Mekong Delta: Economic, Social, and Political Effects of Land Reform in Four Villages of South Vietnam. United Kingdom: Center for South and Southeast Asia Studies, University of California, 1983.

I have yet to see a satisfactory theoretical explanation for why it happened this way in Vietnam but not elsewhere.

Prosterman (1970).

Quoted in Elliott (2010), p. 240. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/corporate_pubs/2010/RAND_CP564.pdf

Quoted in Elliott (2010), p. 235.

Prosterman, Roy L. 1972. “Land Reform as Foreign Aid”. Foreign Policy, no. 6: 128–141.

'Ho Chi Minh enacted a popular but violent land reform, where tens of thousands of landlords were killed and their land was redistributed '??

I doubt that very much.

Ho's friend, Mao, conducted a bloodless land distribution, so I expect that Ho's was too, and that you have simply repeated an Official Atrocity Narrative.