Anatomy of a Coup: Weak States and the Chain of Command

A Development Economist at the Movies

It always shocks me to remember how recent democracy in South Korea is. I was born in 1994. The events of the coup in 12.12: The Day—tanks in Seoul’s streets, gunfights between opposing military factions—occurred just 15 years before I was born, in 1979. 15 years ago from today is… 2009.

The rather drily titled 12.12: The Day—the highest-grossing Korean movie of 2023—depicts how Chun Doo-hwan, South Korea’s military dictator from 1980-7, seized power in a midnight coup, not long after the assassination of the previous dictator Park Chung-hee.1 Chun is possibly the most reviled figure in modern South Korean history, in no small part for ordering the massacre of hundreds of pro-democracy protestors in Gwangju in 1980. It speaks to the trauma of Chun’s dictatorship that 12.12: The Day has sold around 12 million tickets—a quarter of the country’s population.

Unfortunately, as a movie, 12.12: The Day is pretty bang average. Like Ridley Scott’s recent Napoleon, it falls squarely in the genre of the Serious Historical Drama, with title cards announcing the arrival of Important Historical Figures and the passage of Key Historical Events. There are good military guys (the fictionalized Lee Tae-shin) and bad military guys (Chun Doo-hwan) and a chorus of feckless senior bureaucrats gumming up the works.2 At the successful conclusion of the coup, the camera lingers on Chun triumphantly pissing at a urinal, emitting a laugh that Dr. Evil might have thought a bit much. The movie has basically no interest in ordinary civilians, or for that matter women: the only female speaking role beyond a few lines is Lee Tae-shin’s doting wife, who shows up at work to dutifully deliver her husband a scarf, I suppose to remind us that he is, indeed, a Good Guy.

But this is a blog about development, not the movies. Let me slip off my film critic beret, douse my cigarette, and put on the thick-rimmed glasses of political-economic analysis. There were two points relevant to development that I thought 12.12 captured particularly well. (Spoilers follow.)

State Survivorship and Development

The first major theme I got from the movie is the ever-present threat of North Korea, which I think is essential to understanding South Korea’s developmental experience.

A major plot point in the film is if airborne divisions guarding the border with North Korea will be pulled away to join the ongoing coup in Seoul. For the generals on both sides, this is like crossing the Rubicon. Diverting troops from the frontline risked not just escalating the internal conflict, but inviting a North Korean invasion—and, possibly, the extinction of the South Korean state. Invasion was a credible threat. North and South Korea were far closer to military parity in 1980 than they are today; even with the breakneck growth under Park Chung-hee, South Korean GDP per capita only surpassed North Korea’s in 1974.

This points to a central theme of modern East Asian history: that bordering a stronger neighbor threatening to swallow it whole disciplines both political and economic policy. In a classic, Charles Tilly, states-make-war and war-makes-the-state sense, the South Korean state could not afford a Mobutu Sese Seko or a prolonged internal conflict, because otherwise it might cease to exist. Politically, the generals in 12.12 know this and bend over backwards to avoid a full-on shooting war. Economically, it’s also no coincidence that Park Chung-hee launched his famous Heavy and Chemical Industry drive, which essentially built the South Korean steel industry from scratch, just after the United States threatened to withdraw entirely from Asia. (You need a steel industry to make artillery shells and tanks.)

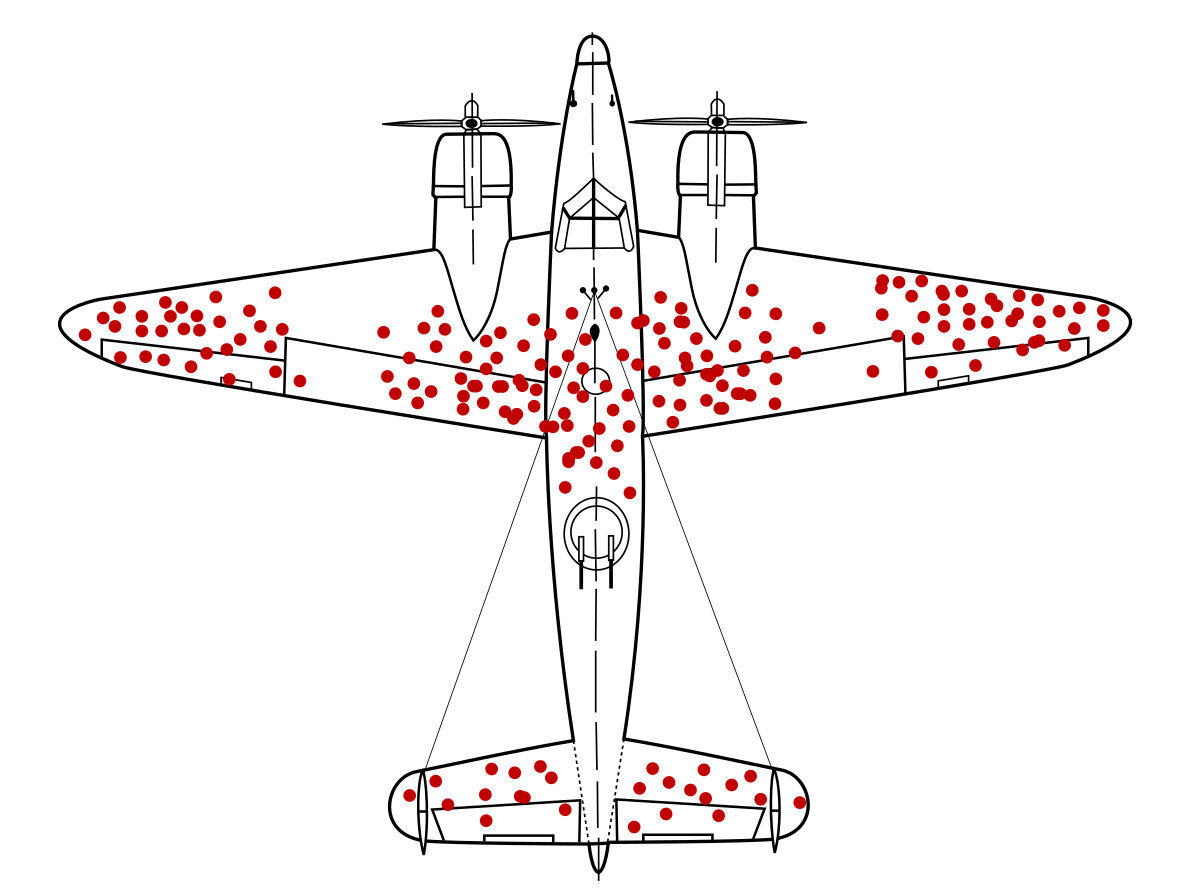

Taiwan, of course, faced a similar peril with Mainland China, which forced the Kuomintang to finally get serious about development. The exception that proves the rule is South Vietnam, the quintessential example of an American Third World client state—which collapsed because it was unable to develop a large enough power base willing to defend it. (My post last week discussed the failure of South Vietnamese land reform.) It’s a bit reductive given how few data points we have, but I’ll say it anyway—there’s a sense in which the developmental success of East Asia reflects a giant experiment in state survivorship, in which South Korea and Taiwan are the winners, and South Vietnam is the plane that didn’t make it back:

The Mechanics of a Coup

But back to the film. (Like Godwin’s Law, all social science discussions seem to lead eventually to the survivorship-bias plane.)

The second major theme, which I think the movie portrayed skillfully and absorbingly, is the actual mechanics of engineering a coup, particularly in a political context with weak institutions. I’m not enough of an expert on the precise play-by-play of the night of 12/12 to comment on its exact accuracy; but the dynamics it portrays are commonplace.

One critical aspect is the importance of informal networks when formal institutions are weak. Chun is the ringleader of Hanahoe, a secret society of officers largely from the 1955 class of the Korean Military Academy. From Gaddafi’s Free Officers Movement in Libya to the Regime of the Colonels in Greece, cabals of disgruntled mid-level officers are a perennial threat to weak regimes.

At one point, with the coup hanging in the balance, Hanahoe officers desperately work the phones, calling every contact they can to convince them to join them. This intervention proves crucial. Subordinates mutiny against their superiors or simply refuse to fight; pro-government forces are literally stopped in their tracks. These informal connections ultimately overwhelm the formal military chain of command.

Another aspect common to many developing countries is the tenuous intersection between civilian and military authority.

As the plot is being hatched, the senior generals insist that they first obtain legal authorization, either from the President or the Minister of Defense—even under Korea’s authoritarian Yushin Constitution, there were at least gestures towards civilian legal authority. Chun needs the generals’ support, and spends much of the coup’s early stages supplicating to President Choi in his office, trying to get him to sign the orders to arrest the Army Chief of Staff, his major obstacle to power. The President refuses. (This refusal is historically accurate.)

The film captures nicely the evolving logic of the plotters. At first, drawn in by promises of promotions and material advancement, they want only a limited sort of mutiny, deposing just the Army Chief of Staff with the formal protection of the law. The crucial turning point is when loyalist officers declare Chun and his allies outlaws, and orders their arrest. The senior generals on Chun’s side, who were skittish about a full-on coup, realize that they have crossed a point of no return.

This helped answer for me why so many military coups go through the hassle of seeking legal authority, when they are the ones holding the guns. Civilian institutions are weak, but not so weak that they can completely be ignored by any individual. When the plot is in its fragile infancy, the generals want the protection of the law, unsure of if they will succeed. (An unspoken assumption, I think, is that the Americans would have something to say about a right-wing coup without at least a fig leaf of legal legitimacy.) Once they are outlaws, the only viable option left is to go all the way, and depose the government.

At the end of the movie, with the loyalist forces neutralized, Chun returns to the President’s office, surrounded by his clique of officers. But by this point, the President’s signature is just a rubber stamp, authorizing events that have already occurred. Chun’s era of military rule has begun.

The Korean title, Seoul Spring, is much better—and more descriptive.

One of the film’s more puzzling decisions is to give historical characters slightly fictionalized names—for instance, Chun Doo-hwan is called Chun Doo-gwang. The magnitude of the change is proportional to how fictionalized the characters are. While clever, it seems clear who the film is depicting, and we should give credit to the audience to accept some dramatization as not the literal truth. Imagine an American film about George Pashington and Timothy Jefferson.

The 'threat' of invasion from the North was never real. It was and is manufactured to keep the Occupied South subject to draconian laws and their comprador enforcers.

Thanks to the South's National Security Law, it is illegal to be a communist or even remotely sympathetic to North Korea. It is illegal in most cases to criticize the government. It is illegal to voice support for some politicians. In some cases these offenses can get you the death penalty.

South Korea's labor law lets companies force employees work 21.5 hours per day. That's 21.5 hours.

43.8% of South Korea’s elderly live in poverty, triple the OECD average rate of 14.8%. Pension or other retirement plan is scarce, and the elderly must continue perform subsistence-level labor late into their lives, facing abuse and awful work conditions.

Life for the lower 50% is better in the North.