"You Can Even Kill Them": Albert Winsemius and the Rise of Singapore

Development and Authoritarianism in the World's Favorite City-State

There are two things that everybody knows about Singapore. One is that it is fabulously rich. The other is that it is a one party-state which subscribes to a meticulous brand of authoritarianism—something to do with chewing gum and the death penalty.

Then, I suppose, there is a third idea, dimly perceived—that the prosperity and authoritarianism are, in some murky but indisputable way, causally linked. It is this idea that makes Singapore globally important, far beyond even its sovereign wealth or GDP.

To be clear, Singapore has elections that are widely regarded as free and transparent, but they have been won entirely by the People’s Action Party over the past sixty years. Opposition parties exist, but tight restrictions on free speech, a close nexus between elites and the state, and electoral rules that favor incumbents mean that they never seriously challenge for power. In a few weeks, Singapore will see just its fourth Prime Minister since independence—and only its second from outside the Lee family.

How did Singapore get this way?

This is a story about a small incident, in a small country, that happened many years ago—but one that illuminates a great deal about development, authoritarianism, and the surprising role of Western advice in shaping both.

Enter Winsemius

The founding father of modern Singapore was Lee Kuan Yew, Prime Minister from 1959 to 1990. Because of Singapore’s success, Lee has become a model for would-be enlightened despots from Kigali to Moscow—a figure of admiration for those who like their development with an extra dose of the cane.1 Lee’s singleminded focus on growth, his intolerance of dissent, and even his stranger proclivities (like his love of trees, or more darkly, his fondness for pseudoscientific race science) have left an indelible mark on Singapore’s design.

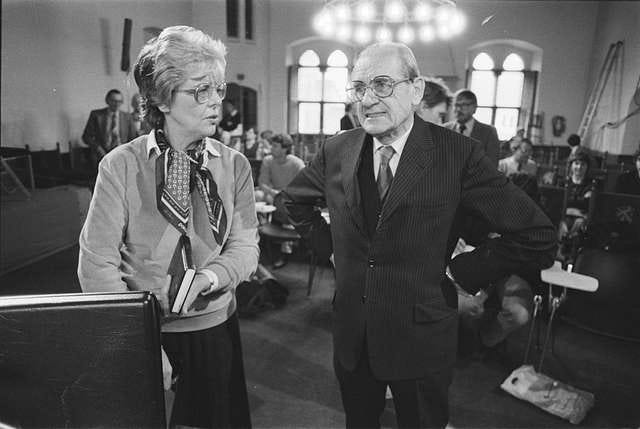

But, next to Lee and his lieutenants, one foreigner has an important claim to the coauthorship of modern Singapore: the Dutch economist Albert Winsemius, who was chief economic advisor for two decades of miraculous growth from 1961 to 1983.

In 1958, Britain granted Singapore internal self-government, and in 1959 Lee Kuan Yew’s People’s Action Party won a strong majority in the Legislative Assembly elections. Prime Minister Lee asked the United Nations to send an advisory mission to help Singapore industrialize.

Winsemius answered the call.

The Winsemius Report

Before coming to Singapore, Albert Winsemius had overseen Marshall Plan spending in the Netherlands, helping his home country rebuild its manufacturing base after the Second World War. He had also advised the governments of Jamaica, Greece, and Portugal, giving him some experience with less developed countries.

In 1960 and then again in 1961, he visited Singapore with a research team to make his appraisal. The product of Winsemius’s two missions was a 1963 UN report, “A Proposed Industrialization Programme for the State of Singapore”.

The central problem was that Singapore needed to create jobs, fast. Winsemius guessed that the unemployment rate was somewhere around 30%, with informal service work like food hawking concealing high underemployment. Rapid population growth, boosted by huge inflows of migration, was only exacerbating the shortage of jobs.

And, in Winsemius’s eyes, the labor problem was not just economic. A strong trade union movement had taken root in Singapore’s working class population, particularly among its Chinese majority. Led by the charismatic Lim Chin Siong, the trade unions were at the vanguard of anti-colonial agitation. Recognizing their potency, Lee Kuan Yew had recruited Lim and the trade unionists into his People’s Action Party (PAP), folding their working-class support into a coalition that won the 1959 election in a landslide.

But because of the popularity of their strong anti-colonial stance, and perhaps because of their ethnic ties to Mao’s China, the labor unions were suspected to have communist links. The early 1960s saw substantial labor unrest; 1961 alone saw 153 strikes. To Winsemius, organized labor represented an existential threat to Singapore’s development project. He recounted in 1982:

It was bewildering. There were strikes about nothing. There were communist-inspired riots almost every day and everywhere. In the beginning, one has to very careful about passing any judgement—one does not know the country, one does not know the people, one does not know the men and women who are trying to steer this rudderless ship. But after a couple of months the pessimism within our commission reached appalling heights. We saw how a country can be demolished by unreal antitheses. The general opinion was: Singapore is going down the drain, it is a poor little market in a dark corner of Asia.

The Winsemius plan sought to strike at the heart of Singapore’s labor problems. Its centerpiece was a “crash programme” to encourage the growth of low-value added manufacturing, like making shirts and underwear, that could absorb large amounts of labor. This, at least, would take some pressure off of unemployment. In the medium run, Winsemius identified key sectors, like chemicals and electrical equipment, in which Singapore might have a comparative advantage. He also developed plans to encourage inflows of foreign capital, like the creation of the Economic Development Board (EDB), which eventually became an important vehicle for promoting investment in Singapore.

The report was sound economics. Winsemius correctly identified Singapore’s strengths—its large stocks of cheap but relatively skilled labor, its strategic position relative to larger export markets—and developed a complementary strategy of attracting foreign capital. And over the next few decades, following the rough contours of this plan, Singapore would grow at breakneck speeds, graduating from low value-added textiles to higher-value added industries, vindicating Winsemius’s basic analysis.

The Winsemius report marked the beginning of a fruitful twenty-year collaboration—a rare happy marriage between foreign advisor and government, in one of the great success stories of rapid economic development.

Operation Cold Store

But there was another crucial component to Winsemius’s advice, that went unmentioned in his official report to the UN.

In his memoirs, Lee Kuan Yew recounts:

I remember his first report to me in 1961 when he laid two preconditions for Singapore’s success: first, to eliminate the communists who made any economic progress impossible; second, not to remove the statue of Stamford Raffles. To tell me in 1961, when the communist united front was at the height of its power and pulverizing the PAP government day after day, that I should eliminate the communists left me speechless as I laughed at the absurdity of his simple solution.2

It's a remarkable admission. Here was a United Nations advisor, telling an ostensibly democratic government to “eliminate” its main political rivals.

In a 1982 interview, which you can listen to on Singapore’s National Archive website, Winsemius elaborated on what he meant by “eliminate”:

… as an economist, I’m not interested in what you do with them. You can throw them in jail, you can throw them out of the country, you can even kill them. As an economist it does not interest me, but I have to tell you, if you don’t eliminate them in government, in unions, in the streets, forget about economic development.

Of course, Lee Kuan Yew’s People Action Party had risen to power in coalition with the trade unions. But it had always been an uneasy alliance, and in July 1961, thirteen left-wing PAP members were expelled after abstaining or voting against a confidence motion in the government. They went on to form their own party, the Barisan Socialis (Socialist Front, in Malay), bringing a hefty chunk of the PAP organization with them. The PAP was left with the thinnest of majorities—26 seats in the 51-seat Legislative Assembly.

True to Lee’s word, the Barisan Socialis were indeed battering the PAP in the legislature, constituting a genuine threat to their hold on power. The common view—held by Lee himself—was that if an election were held before 1964, Barisan Socialis would win.

Compounding Lee’s problems were frustrating negotiations with the British and the Malayans for a potential merger. Lee’s steadfast view was that Singapore would not be viable as an independent city-state; by attaching itself to Malaya, it could ensure its security and guarantee an internal market for its exports. (This diagnosis of course proved incorrect; Singapore was expelled from Malaysia in 1965, and as of 2024 has a GDP per capita that is over seven times higher. But we are getting ahead of ourselves.)

The Malayans were anxious about adding this fractious, strike-prone city to their federation, which would also tilt the ethnic balance away from Malays to Chinese.3 As a precondition to go ahead with the merger, the Tunku of Malaya demanded that Lee deal with Barisan Socialis. The British, the Singaporeans, and the Malays worked out a plan—according to British documents, as early as April 1962, arrest orders for key opposition leaders had been drawn up by Singapore’s Internal Security Council (Jones 2000, p. 91). What they needed was a pretext.

On December 8th, 1962, left-wing, pro-republican forces rebelled against the British in Brunei. Barisan Socialis issued a statement of solidarity with the anti-colonial forces. Lim Chin Siong, it was reported, had also recently met with the leader of the Brunei revolt. It was all that the Internal Security Council needed. “Developments in Brunei had made it necessary to initiate action against the communists,” wrote Lee Kuan Yew in his memoirs, “and the statement by the Barisan supporting the revolt had provided the opportunity.”

The wheels of Singapore’s security apparatus were set into motion. On the morning of February 2nd, 1963, starting at around 3 AM, the police began rounding up suspected communist sympathizers. All told, over a hundred political leaders and trade unionists were arrested and detained without trial. 24 of them were members of Barisan Socialis—including the party’s secretary-general, Lim Chin Siong. Lim would remain in prison for six years, without ever facing trial.

Operation Cold Store, as it became known, broke the back of Barisan Socialis. The People’s Action Party went on to win 47% of the vote in the 1963 general election in September. With most of its leaders in prison, Barisan Socialis still came in second with 33% of the vote.

It remains the best electoral performance by an opposition party in Singapore since independence.

If you seek his monument…

It’s hard not to see Cold Store as a foundational event in Singapore’s constrained political life, where critics of the government are routinely sued into oblivion for ordinary acts of political speech, and the gnat-like opposition can never seriously challenge the PAP’s monopoly on power. Even the study of Cold Store itself remains politically sensitive topic—in 2018, the historian P. J. Thum was subjected to six hours of critical questioning in Parliament for his research.

The official purpose of Cold Store was to “safeguard against any attempt by the Communists to mount violence or disorder in the closing stages of the establishment of the Federation of Malaysia”. Sixty years on, the Singaporean government has not released any evidence demonstrating Barisan Socialis’s communist links, citing the need to maintain the confidentiality of its sources (most of whom are now dead). With no evidence forthcoming, it is impossible for any independent researcher to verify claims of a communist plot. For their part, contemporary British sources concluded that evidence that Barisan Socialis leaders Lim Chin Siong and Fong Swee Suan were communists was “very stale”, noting further “that there has been no recent proof of Communist activity or allegiance on their part” (Jones 2000, p. 92).

Now, was Winsemius’s advice really decisive? Probably not. With Barisan Socialis a political thorn in the side of the PAP, and the Malayans demanding their elimination as a precursor for merger, Lee didn’t need more reasons to get rid of them. But it is certainly remarkable that the first mention of the idea to eliminate Singapore’s political opposition, both in Lee’s recollection and Winsemius’s, came from this foreign economic advisor—a representative of the United Nations. If Winsemius deserves credit for envisioning Singapore’s economic miracle, he also shares responsibility for conceptualizing its authoritarian political turn.

Perhaps, without the crushing of it militant labor movement, Singapore’s headline growth numbers posted through the 1960s and 70s would have been less impressive. In the 1960s, when Fairchild Semiconductor—a precursor to Intel—was deciding where to place its second Asian factory (after Hong Kong), it chose Singapore for its low labor costs.4 Wages in Singapore were 11 American cents an hour, compared to 25 cents in Hong Kong, 19 cents in Taiwan, and 15 cents in Malaysia. A Fairchild semiconductor employee noted approvingly that the country had “pretty much outlawed” unions.

But it’s also possible to imagine a different path for Singapore, one perhaps with a little less headline growth, but one with a little more attention to those at the bottom of the income distribution, and—most of all—one where a thriving opposition can keep the government accountable. Instead, what Singapore got is an authoritarian party-state that, while responsive to the people’s needs, is never at serious risk of losing power—an example not lost on Deng Xiaoping when he visited in 1978.

Sixty years on, Singapore, next to China, has become one of the world’s bywords for authoritarian development. That it ever had a vibrant political opposition now seems almost unthinkable. That Western hands, too, had some authorship in the disappearance of this opposition, has been lost in time. Like learning that the Sahara was once an ocean, it simply doesn’t register beyond a remote intellectual level. The slate has been wiped clean.

Thank you for reading. Please consider subscribing to Global Developments to receive more regular essays on global economics, development, and poverty. Some recent posts:

A historical deep-dive into the role of economists—and statistical malpractice!—in prolonging the Vietnam War

Analysis of the developmental effects of the CFA franc—“Africa’s last colonial currency”

The early life of Albert Hirschman—resistance hero and development economist—and his remarkable Strategy of Economic Development

In the original 1960s Star Trek, “Lee Kuan” is listed as one of the great conquerors of Earth’s history.

Lee Kuan Yew, The Singapore Story, p.

North Borneo and Sarawak were eventually added to solve the latter problem.

Chris Miller’s Trade War, p. 54.

As a Singaporean, I thank you for bringing this piece of history to light. It's a vital topic to keep alive, precisely because it's so morally ambiguous. Another stereotype of my country's politics besides being authoritarian is that of ruthless amoral pragmatism. The ends justify the means. Perhaps destroying the lives of so many individuals was a cruel set of means, but if the end was a secure and prosperous Singapore? Worth a ponder, regardless of which side of the balance you eventually fall on.

I really enjoyed this read, thanks Oliver. It's nice to see the moral ambivalence, as the question is: is the end goal democracy and representation or is the end goal good governance and higher quality of life for the majority of a nation's citizens?

Also, it's interesting to note the downside of high material prosperity: Singaporeans have the highest unhappiness rates in the world and among the lowest birthrates. Compare to Malaysia, much poorer but much happier and with a much higher fertility rate...perhaps there's more to life than GDP numbers.

I covered some similar terrain focusing on Lee Kuan Yew's philosophy in this post: https://neofeudalreview.substack.com/p/lee-kuan-yew-and-singapore-a-knife