A World Without Aid?

A Look at USAID Historical Data

Most of my readers are likely deeply concerned about the wholesale destruction of USAID. They don’t need to be convinced further with statistics—that 19 million lives have been saved by PEPFAR, that 434 of 634 vital soup kitchens in Khartoum will have to shut down, that $500 million of food aid is stuck rotting in warehouses rather than going to the hungry.

Just to lay all my cards on the table, I’m gutted.

Ken Opalo, Lauren Gilbert, Kelsey Piper, among others, have already done an excellent job analyzing the developmental and humanitarian consequences of this rollback. Pushback has begun, as have attempts to mitigate the damage.

Of course, there’s almost no way to fill a $72 billion hole, and with the full force of the Trump-Musk movement concentrated on USAID, it’s clear that the political terrain around aid has been fundamentally altered. Moreover, the same impulses that are driving the defunding of USAID will soon gear up in other rich countries.

As the initial shock has worn off, and as the longer-term implications have become clear, in this short post I thought it would be worth taking a step back to think about US AID in broader historical perspective.

Weeks Where Decades Happen

Let me do my best Adam Tooze impression and say that the last few weeks represent an epochal break with basically the entirety of post-World War II American foreign policy.

Looking at the official spending data from ForeignAssistance.gov, the striking fact is the remarkable stability of American aid spending in real terms since 1945:

Yes, there have been fluctuations, but look at the scale: for the better part of a century, aid obligations have hovered around a $40-80 billion band. Remarkably, the year the US spent the most in dollar terms on aid was… 1948.

Even as GDP has grown tenfold, US aid budgets have remained basically flat in real terms—the result (one might guess) of a delicate balancing act between bipartisan consensus among elites and a wariness of attracting too much negative attention. The longevity of that consensus is itself remarkable: in 79 years of data, Republican presidents spent an average of $34 billion a year on aid, while Democrats spent $40 billion. For all the stereotypes of bleeding-heart liberalism, the largest modern ramp-up of foreign aid occurred under a Republican, George W. Bush, who launched the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR).1

In a few short weeks, that political equilibrium has now been disrupted, I fear permanently.

What Aid Can Accomplish

Measuring the empirical effect of aid on development is a real hornet’s nest, which I can’t do justice to in this post. But it’s worth reminding ourselves what, in the best-case scenarios, aid can accomplish.

A few weeks ago, I wrote about the enormous differences in starting conditions between newly independent East Asia and Africa, that sent them on vastly different developmental trajectories.

All that still holds true, but I could have just as easily written about the historical gap in their incoming aid flows. Amid all the debate about industrial policy and Confucian culture, the sheer quantity of American aid to Korea and Taiwan often gets lost in the discussion about what set East Asia apart.

Well into the late 1970s, South Korea was getting as much American aid as all of Sub-Saharan Africa combined:

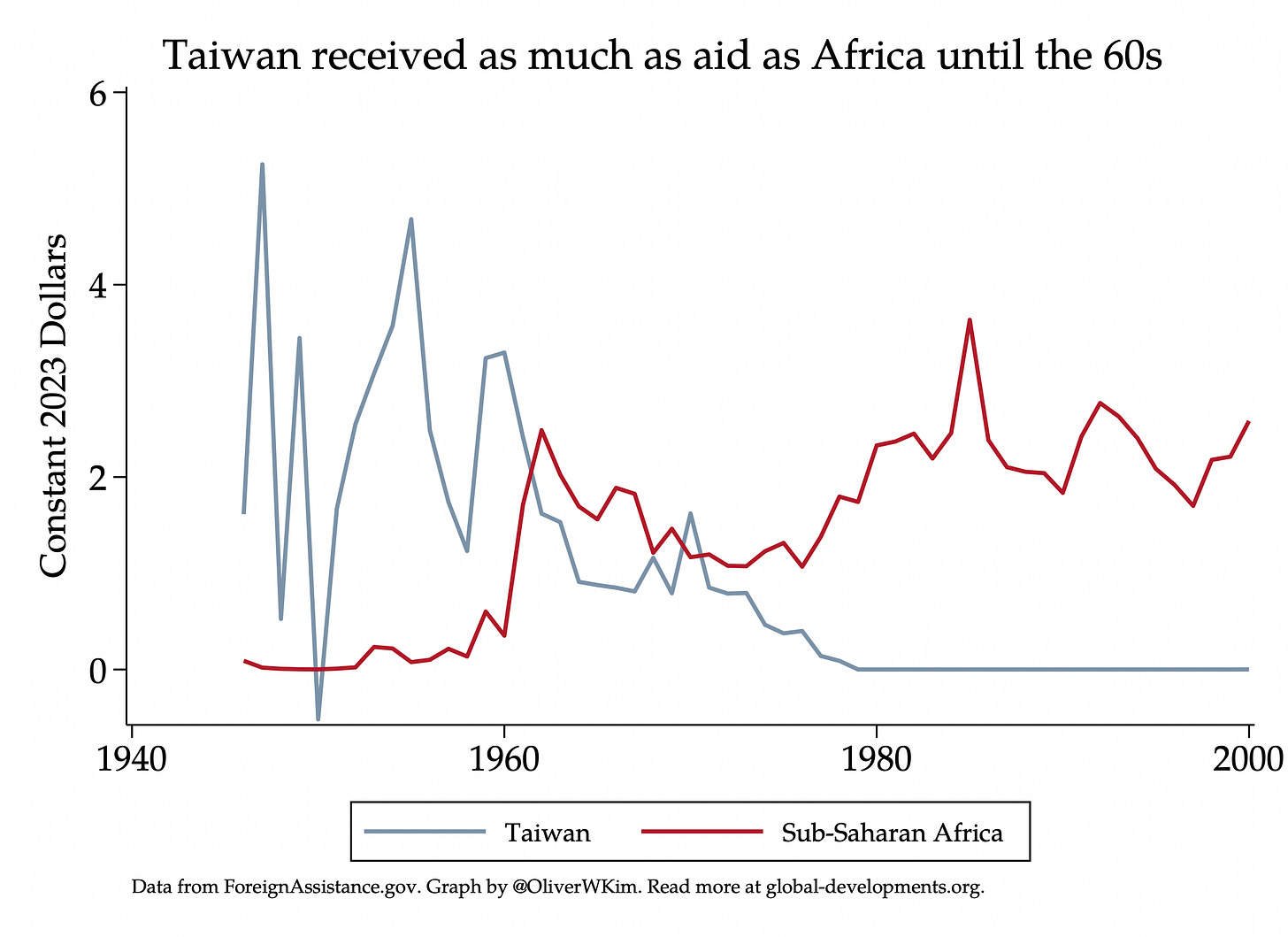

Just as Taiwan was into the early 1960s:

Am I claiming that American aid was the main factor behind the East Asian Miracle? No. (Before you start typing in the comments, read last month’s piece.)

Much of this was military aid, and pretty useless for economic development. If the volume of American aid were the sole determinant of growth, then the developmental champion of the 20th century would have been a country that no longer exists: South Vietnam, which absorbed half ($20 billion) of all American aid spending in 1973.2

But take it from an expert in the niche subfield of 1950s Taiwanese development: American aid helped a lot, too. In both countries, food and military aid supported countries which might not otherwise have survived. In Taiwan, it was American funding of the Joint Committee on Rural Reconstruction that enabled the famous 1950s land reform, and paid for an army of agricultural extension workers to canvas the country spreading best practices. (It was the latter, more than the former, which likely kickstarted Taiwan’s agrarian development.) In South Korea during the late 1960s, USAID gave technical assistance to the infant export industry, and USAID procurement contracts helped provide a crucial demand stimulus for Korean firms. (Keep an eye out for my ongoing research with Nathan Lane, Philipp Barteska, and Seung Joo Lee on this topic.)

All this to say: capable states with ambitious developmental plans, when hit with a bazooka of money, can seize the opportunity to transform themselves.

A World Without Aid?

Of course, states capable of emulating Korea and Taiwan have turned out to be pretty rare. As scholars like Nicolas van de Walle have pointed out, aid can also foster an unhealthy dependency—in his coinage, many African states live in a state of “permanent crisis”, where aid is large enough to reshape (and warp) the political economy around it, but not large enough to be fundamentally transform countries’ economies.

American aid obligations in Sub-Saharan Africa, for instance, have never exceeded $15 per person:

Of course, not all that money was spent effectively. But a solid chunk—roughly $5 of those $15—went to PEPFAR, one of the most effective public health programs around. And even if you poured the money into the highest-return, most cost-effective programs, $15 is still not a whole lot—less than 1% of Kenyan GDP per capita, or likely less than 3% in Malawi.3 In the early 70s, South Korea got more like $180 in 2023 dollars, or closer to 10% of GDP per capita.

The potential end of USAID is an unfolding public health and humanitarian disaster, but it does not permanently doom the task of growth—in large part because these aid flows were far too small to begin with. For people like me working on global development in the West, the bitter pill to swallow is that aid is not development. NGO leaders and aid workers and development economists were never the protagonists; the key players are still there, in their home countries, scrimping and saving and hustling, and the task ahead for them remains largely unchanged.

A world without aid is closer than you think—because we’ve been living so close to it this whole time.

Note (Feb 12, 2025): an earlier version of the first graph understated post-2000 aid. Thanks to Lauren Gilbert for pointing this out.

It’s one of history’s strange incongruences that the modern American president responsible for the most needless death was also probably responsible for saving the most life.

When you’re done reading that last piece, read my post from last year on how statistical malpractice analyzing the effects of land reform contributed to the prolonging of the war.

See my screed on how unreliable these GDP numbers are.

What is the unit of the figures (Korea + Sub-Saharan Africa, Taiwan + Sub-Saharan Africa...)? Dollars, ok, but billions of dollars, right?

Oh, also assume you’ve seen the new Lant chapter on if aid helps: https://lantpritchett.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Development-Happened-Did-Aid-Help-handbook-chapter.pdf