Twilight of the Econs?

What Does the Faltering Econ Job Market Mean?

A story getting covered in The New York Times is usually a lagging indicator: a good way to learn that something horrible has happened, long after you could conceivably profit from the news.

So it was an ill portent when, earlier this month, The Times finally wrote about what’s been going wrong with the job market for economists:

… Universities and nonprofits have scaled back hiring amid declining state budgets and federal funding cuts. At the same time, the Trump administration has laid off government economists and frozen hiring for new ones.

Tech companies also have grown stingier, and their need for high-level economists — once seemingly insatiable — has waned. Other firms have slowed hiring in response to the economic uncertainty introduced by President Trump’s tariffs and the possibility that artificial intelligence will replace their workers, even if those workers have a doctoral degree.

On a normal day, this blog is about the poorest people in the world. The median economist made $115,440 in 2024. Until recently, this was a profession with an employment rate of 100%. Most people might ask: why should we care?

Of course, I’m selfishly interested—it’s a bit harrowing when your chosen profession is nuked from orbit. (With the gutting of USAID, development economics has been particularly hard-hit.)

But there are more dispassionate reasons to care. Among academics, Econs are unique for the power we wield. We control the financial weather; we recommend bombing campaigns to presidents. The market for Econs (with all its institutional strangeness) is more than just a potential curiosity for anthropologists; it puts its unmistakeable stamp on the systems of knowledge and expertise that, without exaggeration, have governed the postwar global order.

This post explores this looming crisis, in two parts. Is this down labor market really the Twilight of the Econs? And what does this mean for Economics as a science, and how Economics acts upon the world?

What’s Going On With The Econ Job Market?

Even before the cuts to the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health, the economics job market was cooling.

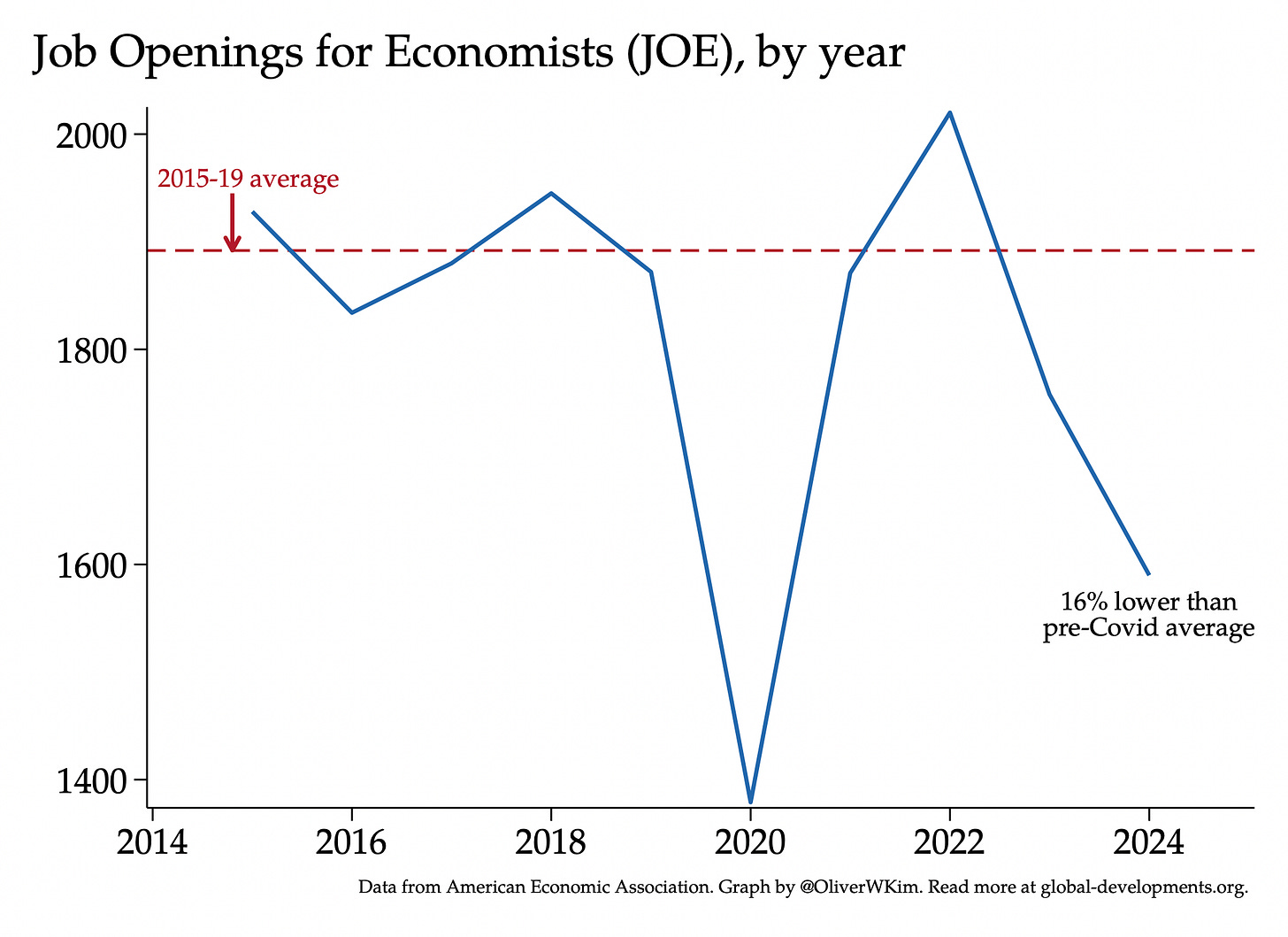

The number of openings each year from Job Openings for Economists (JOE), the American Economic Association’s centralized job board, have fallen precipitously over the past two years:

In the halcyon days of 2015-19, openings on the economics job market hovered at around 1900 per year. In 2020, Covid was a major shock, but the market bounced back quickly in 2021 and 2022. Since then, though, the market has clearly been in a funk. 2023, my job market year, saw a sudden dip in postings. 2024 was even worse, with openings falling 16% lower than the 2015-19 average.

At the time, the sudden fall in 2023 seemed mysterious—it was an otherwise healthy year for the broader labor market. In hindsight, it seems like the 2021-22 recovery masked some underlying weakness. The 2020 job market had 500 fewer openings than the 2014-19 average; 2021 and 2022 together produced only around 100 more jobs than the 2014-19 average. In other words, the recovery never made up for the pandemic; by this crude logic, around 400 economist jobs were “destroyed”.

Economists like to think of themselves as exceptional (more on this in a minute), but this slowdown is part of a general decline in academic hiring. Disciplines like history and anthropology have been suffering for some time, with the production of PhDs outpacing the number of tenure-track jobs. Life in STEM is not much better; by one calculation, only 13% of PhD graduates will land a tenure-track position in the United States. The drying-up of tenure lines has led to the “adjunctification” of the academy, with more university courses taught by lower-paid, contingent workers.

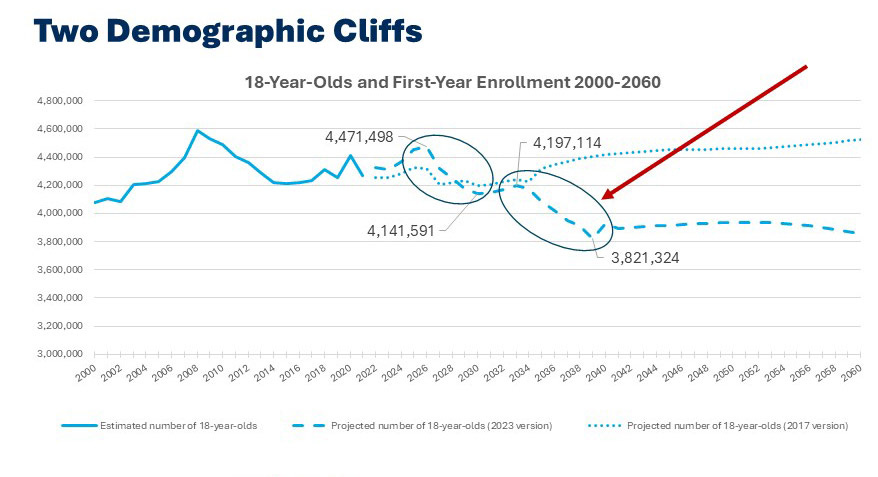

I still haven’t seen a convincing empirical breakdown of how much over-supply versus under-demand have driven the breakdown of the academic market. But surely an important overarching factor is the demographic decline in the number of college-age adults, a trend that will only accelerate over the next decade:

And of course, all of this decline occurred before the litany of disasters that have recently hit the Econ job market. In May, Jerome Powell announced that the Federal Reserve—perhaps the largest employer of economists in America—would cut its workforce by 10%. The federal government has frozen hiring, as has the World Bank. Hit by the dual threat of fines and looming cuts to federal funding, Harvard, MIT, the University of Washington, Notre Dame, Northwestern University, among others, have announced hiring freezes and budget cuts.1

The 2025 market has not yet started in earnest, but the early indications are bad. Job postings are currently below those at the same point in 2023 and 2024:

A potential 20% drop in the job market is a serious historical shock, and a moment to pause and take stock of what is at threat. What does it mean to be an economist in 2025?

What Does It Mean To Be an Economist?

The best answer to that question remains Marion Fourcade’s 2010 classic Economists and Societies, a comparative sociology of the economics profession in America, Britain, and France.

Fourcade’s central point is that, far from being a universal science, the profession and practice of economics reflect the societies in which economists live. This is news perhaps only to economists. But “mere” description can be quite illuminating, because it reminds us that things do not have to be this way.

In Britain, midcentury economics was the province of gentleman scholars, who often lacked formal credentials but influenced policy through intra-elite personal networks. (Keynes and Kaldor are exemplars.) In France, postwar economics developed from the tradition of state engineers, growing out of a cadre of public managers and technicians trained by the administrative state. It was in America that the Economics PhD first emerged as a professional credential—a union card if you wanted to be a serious policymaker.

How did this come about? Fourcade describes how, in the early 20th century, demand for technical expertise and the forces of academic hierarchy interacted to produce a discipline with an unusually tight grip on the bounds of orthodoxy:

In the opening decades of the twentieth century, public officials in the American administrative institutions at the local, state, and federal levels created demand for unpoliticized, technical expertise mostly drawn from the academic professions… In the absence of an elite of public technocrats… they explicitly relied on academic economists to carry out technical tasks… This created a strong institutional basis for an economics profession that is profoundly rooted in the academic world, and in the imperatives of empirical relevance and scientific quantification. A small elite of professors within top universities exerts efficient control over the rest of the field and defines the boundaries of what constitutes acceptable economic expertise. Commanding widespread respect (both nationally and internationally) from the lower strata of the field, it also holds institutionalized access to prestigious appointments in government and international organizations (pg. 8).

Let me offer a couple of observations, particularly for non-economists, to underline the strength of the academic economic hierarchy—and its connection to the levers of power.

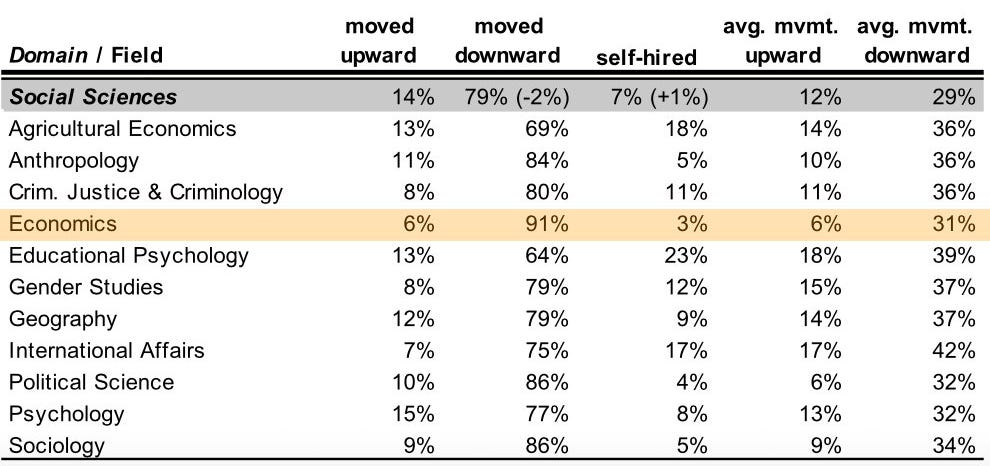

According to a 2022 study in Nature, 6% of academic economists place at a higher-ranked school than their PhD, third-last among all fields after Classics & Religious Studies, and less than half the average for social sciences:

Concentration only gets higher at the top of the profession. By my count, only one out of the last 25 presidents of the American Economic Association was from a program outside the top ten—Tom Sargent, at NYU. By comparison, the American Political Science Association had twelve.2

Why is prestige so concentrated in a few top departments? Surely a large part of this is that economists at top departments are smart and work frankly insane hours. But surely another part is institutional. Promotion and tenure are largely determined by publishing articles in prestigious journals, but editorial boards are dominated by professors at top schools. In the extreme, two of the Econ’s Top Five are “house” journals, Harvard’s Quarterly Journal of Economics (QJE) and Chicago’s Journal of Political Economy (JPE). Bethmann et al (2023) find that QJE articles by authors with ties to Harvard and MIT are cited systematically less than those by authors from other top 10 schools. If citations are a crude proxy for article quality, this suggest some measure of home bias—as if the Yankees got to change out of their uniforms mid-game and call balls and strikes.

(Interestingly, JPE articles by authors affiliated with Chicago are cited systematically more.)

This kind of minutiae matters because, as Fourcade describes, academic hierarchy is tightly intertwined with the apparatus of American government. The most powerful instance of this is, of course, the Federal Reserve, which has largely been staffed and led by PhD economists from top programs.3 With its near-instantaneous influence on global financial conditions, there is no remote equivalent for political scientists or sociologists. (It’s worth meditating on how strange a sociology equivalent in government would seem—which, on further thought, makes the Fed seem even more remarkable.)

Then, on top of the Fed, there is the glittering march of star advisors to the White House—the Galbraiths and Rostows, the Furmans and Summerses. The joke was that every time a Democrat won the Electoral College, Harvard’s Littauer Center would have to start looking for guest lecturers; for a time, with Marty Feldstein and Greg Mankiw, this was even true for Republicans as well. At the risk of being charged with first-degree name-dropping, my own experience in academia reflects this extreme concentration. As a Harvard and Berkeley grad, the last four chief economists of the International Monetary Fund were all at one time my professors. (Incidentally, Marion Fourcade is married to Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, the current Chief Economist.)

That institutional power and academic prestige should be so intertwined deserves some pause.

The Electric Kool-Aid Market Test

But the technocratic-academic nexus (say that five times fast) is not the only thing that makes American economics so unique, or so hegemonic. Its second characteristic might be called the Market Test. Fourcade again:

The combination of the definition of the economist by a technical, measurable form of competence, of a certain consumer orientation within academic institutions, and of institutionalized competition among professions has produced a situation where economic knowledge has been more “market-oriented”… than elsewhere…. The inscription of American economics in the market system has served as a basis for a gradual expansion of the profession’s jurisdictional claims, through the commercialization of economic ideas and tools (pg. 9).

Put crudely, the one thing economists could always lord over other academic disciplines was their employability. During a golden age that spanned somewhere from prehistory to around 2019, economists were in hot demand from consultancies, investment banks, and tech companies. This raised wages (economics professors make more than other academics), and soaked in talent which otherwise might have gone to other disciplines. It speaks to the level of security (and entitlement) of that era that the running advice to prospective PhDs was that if you flamed out of the academic job market, you could at least settle for a job at Facebook.

With the fall in job postings, we Econs are sounding a lot less smug.

Between threats to Fed independence, cuts to academia, pullbacks in industry, the institutional features that Fourcade argues enabled the ascendance of American economics—the technocratic deference to economists in government and the demand for economic tools in the private sector—are all currently at risk, in a way that they never were in the 20th century.

An additional complication, which raises the stakes, is that the American system of economics has conquered the world. Fourcade’s book came out in 2009. Since then, much of the distinctiveness of the national economicses in her account has been flattened out. The Paris School of Economics has emerged as one of the world’s leading departments, regularly placing students in top American jobs. Oxford and Cambridge’s training, after some resistance, has converged with the American model. (LSE was an early adopter.) The European academic job market and the American job market are now joined at the hip; applying for jobs in both is trivial.

In short, as usual, America won.

But this convergence now exposes the profession to common shocks. My sense is that supply of US-style, non-US trained economics PhDs has recently increased. (Unfortunately I wasn’t able to wrangle the European data to confirm this; if you can get this to work please reach out.) If those positions were created with the expectation that American demand would soak up supply, the market has a rude awakening on its hands. The looming crisis of the Econs is not American, but global.

What Is To Be Done?

In any crisis, there’s a temptation to blame impending downfall on one’s sins. Perhaps economics got too woke and invited right-wing backlash. Or perhaps it got lost in a fog of frictionless theorizing, and was caught flatfooted by the surprises of the Great Recession, the China shock, the Trump election, and the Trump election.

Close readers of this blog will note that I’m fairly ambivalent, even critical, about the overall impact of my field. But none of these theories quite ring true to me.

Economics may have given birth to neoliberalism, but—if Fourcade’s account is right—its ascendance was also the product of social forces far larger than any academic discipline. The expanding 20th century American state needed a source of technocratic expertise in economic governance, and academic economists happened to elbow out the other contenders—the lawyers, the businesspeople, the political scientists, the sociologists—to supply it. Put simply, nothing says that the economic policy has to be made by professors. The mid-21st century may chart a different course.

What about the more urgent question I started with. Do I think the PhD job market will bounce back?

Prognosticating too eagerly is a good way to land yourself a place in the Irving Fisher Hall of Forever Being Remembered For Having Said One Stupid Thing.4 A 16% fall in jobs, while devastating, is not yet apocalyptic. (By comparison, historian job ads have fallen closer to 50% since their 2008 peak.) But for things to get better requires a causal mechanism. Reinstating science and academic funding would require either Republicans to reverse their stance on the value of higher education, or for Democrats to win back the Senate. I don’t have a great sense of if either will happen.5

In this case, prediction may be less important than preparation. Placement chairs need to own up to the harshness of the labor market, and urge job market candidates to start prepping non-academic options. (Better yet, admissions chairs should consider paring back cohort sizes.) Candidates who would like a proper job after graduating should be networking, hard. And candidates resolutely committed to academia should steel themselves for long hibernations as post docs, to wait out the coming storm.

On second thought, I will venture one dark prediction, for at least the near future.

We’re going to see a lot more Substacks.

PS: If you’re on the market this year, and would like to chat, please reach out. You can DM me on Twitter at @oliverwkim.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy:

A historical deep-dive into the role of economists—and statistical malpractice!—in prolonging the Vietnam War

The early life of Albert Hirschman—resistance hero and development economist—and his remarkable Strategy of Economic Development

“You Can Even Kill Them”: a UN development advisor’s role in shaping Singapore’s development—and its authoritarian turn

Some of these hiring freezes may be restricted to staff; the University of California system has a “hiring freeze” in effect but can still hire faculty.

My spreadsheet calculations here. I used the top 10 program rankings from the 2025 US News and World Report.

Jerome Powell is a lawyer, but Ben Bernanke was a Princeton professor and Janet Yellen a professor at Berkeley.

Fisher, America’s leading economist, in 1929: “stock prices have reached a permanently high plateau”.

In a hopeful note, the most recent House Republican budget maintains the National Institutes of Health budget at $47 billion.

Excellent piece.

On elitism in the US econ profession, see also “Who runs the AEA?” by K. Hoover and A. Svorencik in the J. of Economic Literature, 2023.

part of the explanation, in my view, is that the sociology of econ that Fourcade describes so well has calcified, become sclerotic -- that CS is taking more of the best human capital, and that Economists are wasting more and more of their total effort on their internal signalling game. This could bite in academic hiring if deans etc realize that economists are very expensive and no longer as central to overall university prestige https://kevinmunger.substack.com/p/wither-economics